by Lynne Chia (Feeding City Team Alumni)

On November 17, 2020, Singaporeans celebrated the news that local hawker food culture was one step closer to being inscribed on UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage list.i This year, however, has not been easy for this treasured facet of Singaporean society. Hawker food refers to cheap and delicious local foods sold at open-air centres across Singapore.

It has a rich history that spans across a century of complex developments between a country and its people. Singapore’s status as a port-city in the twentieth century brought about an influx of immigration mainly from China (southern provinces of Fujian and Guangdong), India (Tamil Nadu) and the Malay Archipelago, to work and live in the ports, mines, plantations and emergent villages and towns.ii

Quick and affordable meal options became a necessity for the average immigrant worker. This gave rise to street hawkers who took up food trades to earn a livelihood. They set up makeshift stalls along roads and places around the growing urban areas of Singapore. Over time, this hawker food culture developed a unique identity of its own; informed by a multi-cultural palette of flavours and heritage, and became tied intrinsically to the lives of ordinary Singaporeans till this day.

The unprecedented consequences of COVID-19 have left a significant mark on hawker culture in Singapore. Over the past decade, hawkers have been struggling with rising prices of fresh produce and stall rental costs. The outbreak of COVID-19 has only served to place more intense pressure on the Singaporean hawker trade. The introduction of the government-coined “circuit-breaker” measures on 7th April 2020 was Singapore’s cordon sanitaire implemented due to the burgeoning COVID-19 cases from clusters at foreign worker dormitories.

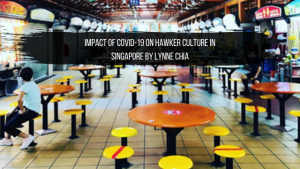

With these measures in place, hawker centres, traditionally the centre of community life for many, became off-limits except for takeaways and deliveries. The familiar lunch-time office crowds and late-night supper groups were reduced to a trickle in most places, as residents were strongly urged to stay home–barring exercise and shopping for essential items.

by Lynne Chia (Feeding City Team Alumni)

On November 17, 2020, Singaporeans celebrated the news that local hawker food culture was one step closer to being inscribed on UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage list.i This year, however, has not been easy for this treasured facet of Singaporean society. Hawker food refers to cheap and delicious local foods sold at open-air centres across Singapore.

It has a rich history that spans across a century of complex developments between a country and its people. Singapore’s status as a port-city in the twentieth century brought about an influx of immigration mainly from China (southern provinces of Fujian and Guangdong), India (Tamil Nadu) and the Malay Archipelago, to work and live in the ports, mines, plantations and emergent villages and towns.ii

Quick and affordable meal options became a necessity for the average immigrant worker. This gave rise to street hawkers who took up food trades to earn a livelihood. They set up makeshift stalls along roads and places around the growing urban areas of Singapore. Over time, this hawker food culture developed a unique identity of its own; informed by a multi-cultural palette of flavours and heritage, and became tied intrinsically to the lives of ordinary Singaporeans till this day.

The unprecedented consequences of COVID-19 have left a significant mark on hawker culture in Singapore. Over the past decade, hawkers have been struggling with rising prices of fresh produce and stall rental costs. The outbreak of COVID-19 has only served to place more intense pressure on the Singaporean hawker trade. The introduction of the government-coined “circuit-breaker” measures on 7th April 2020 was Singapore’s cordon sanitaire implemented due to the burgeoning COVID-19 cases from clusters at foreign worker dormitories.

With these measures in place, hawker centres, traditionally the centre of community life for many, became off-limits except for takeaways and deliveries. The familiar lunch-time office crowds and late-night supper groups were reduced to a trickle in most places, as residents were strongly urged to stay home–barring exercise and shopping for essential items.