PRELIMINARY RESEARCH INTO CONTEMPORARY ROCK-HEWN CHURCH MAKING IN ETHIOPIA

by

Michael Gervers (University of Toronto)

While art and architectural historians have, over the past century, made long strides in documenting and interpreting Ethiopia’s impressive repertory of rock-hewn churches, not a single publication has been wholly dedicated to contemporary examples of this ancient craft. The first to draw our attention to the subject was Paul Henze who, in 1993, was introduced to a new rock church which was being hewn at the time by aläqa Halefrom Retta as a replacement for the much earlier rock-cut counterpart at Peṭros wä-Pawlos (Ṣäᶜada Ǝmba, Təgray). Henze reported his discovery in a presentation made to the Third International Art Conference in Addis Ababa in the same year. In 1997, he documented a second church, Čäčäho Gäbrəᵓel, which was underway on the west side of the gorge separating Wällo from Gayənt in Gondär. The work was being conducted by several dozen laborers, then paid five birr a day, under the guidance of Abba Gəbrä Ṥəllase Defar Sema. In the same year, he also visited a new rock church site at Ǝtissa in Ṥäwa, the

birthplace of St. Täklä Haymanot, where 23-year-old baḥtawi Gäbrä Maryam [Fig.01], now 41, had been working six days a week for nearly three years. By way of conclusion to his notes, written in 1997, Henze wrote: “The oppressiveness of Derg rule generated a resurgence of religion in Ethiopia. The process has not yet lost momentum. The cutting of new rock churches should be seen as a manifestation of this trend.” The question is, whether the phenomenon is a continuation of an ancient tradition, or a revival thereof.

In March 1999, in notes which he prepared for his frequent traveling companion, Stanisław Chojnacki, Henze reported having seen

four new rock churches carved by the late grazmač Ḫaylä Darge in the Säraye region and located 8 km north of Däbrä Bərhan in Šäwa. The upper church was called Säraye Mikaᵓel, and the lower three in the gorge, Talas Ǝgziᵓabəḥer Ab, Betä Maryam and Betä Ṥəllase. The site is extremely popular today among pilgrims from Addis Abäba, who come away with pulverized holy rock dust known as ‘ṣäbäl.’ Photography there is restricted.

The new church near Peṭros wä-Pawlos cited by Henze was more precisely identified by David Phillipson, who described it as t

he church of Petros at Mälähay Zängi, and the excavator as Abba Halefon Teka. Excavation is reported still to have been underway in 1997 and in 2000, and completed by 2006. He reported that in the same year excavation of a new ‘hypogeum’ had begun in the Amhara region, in the Näfas Mäwčha area. This may well be the church of Čäčäho Gäbrəᵓel to which Henze referred. Fr. Emmanuel Fritsch has pointed out other places of potential interest, including “some church being hewn by a neighbouring community” near ᶜAddigrat, and three

churches carved out of the rock by the young hermit, märigeta Gäbrä Mäsqäl Täsämma at Ambager (woreda: Wadla), near the crossroad on the Chinese Road at Gašäna in Lasta (Fig.02).

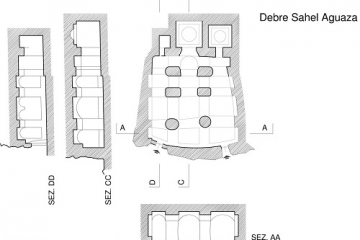

With these and several other potential sites in mind, I made my way to Mäqälä in February 2015 as a point of departure to pursue the subject of contemporary rock-hewn churches in Təgray. I had myself seen in 2007 a new church at Agᵂäza [Fig.03a; Fig.03b] in the Gärᶜalta mountains which I was told at the time had been crafted by a priest from Ḥawzen called märigeta Zeberhan (+2015). Ḥawzen was already on my list, therefore, when a chance enc

ounter with Professor Ayele Bekerie of the History Department at Mäqälä University led me to the master craftsmen of rock-hewn churches, Gidäy Hadush, who had carved his own home out of the rock on the southern edge of the town. This rock-hewn home had been noticed by the priest from the village of Ǝnda Maryam in the Edaga Hamus region of Temben (Wäräda: Wärk Amba; Tabia: Santa Gäläbäda). This priest, qäsis Gäbrä Giyorgis, invited Gidäy Hadush in about 2006 to make a

rock-cut church in his village. A contract was settled on for 60,000 birr, but it was too little and after two years Gidäy was bankrupt.

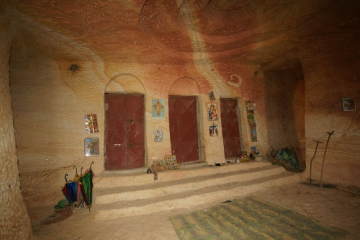

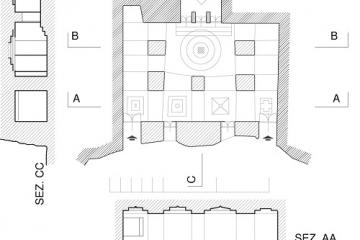

He and his team were obliged to abandon the job, which in the end was finished by village locals who by that time had become familiar with the work. Since then, this Gidäy Hadush has worked predominantly at Maryam Mawka [Fig.04; Fig.05a; Fig.05b], near the road leading from Ḥawzen to ᶜAbiy ᶜAddi (Tämben), a church which has since been completed. He now is involved in the carving of May Wäyni Ǝnda Giyorgis on the outskirts of Ḥawzen

[Fig.06]. The job will, he says, cost 1,000,000 birr to complete, largely because the rock there is harder to carve than at Ǝnda Maryam.

Gidäy Hadush reported that work on this project had been halted due to the shortage of funding, but when I visited the site I found a team of eight workmen busily chiseling away [Fig.07] under the watchful eye of qäññ geta Ḥagos Gäbrä Ǝgziᵓabəḥer, ‘fighter’ and treasurer of the church committee [Fig.08]. Ḥagos had himself been a workman, so he knew the trade, but the master craftsman who had brought them to this still early stage of the project was Gidäy Yəheyyəs Ǝmbayyä [Fig.09]. For Gidäy Yəheyyəs, at age 48, May Wäyni Ǝnda Giyorgis was his fourth rock-hewn church, all of them situated in and around Ḥawzen Gärᶜalta. He, like Gidäy Hadush, was not employed at that moment for the same reason: lack of funds.

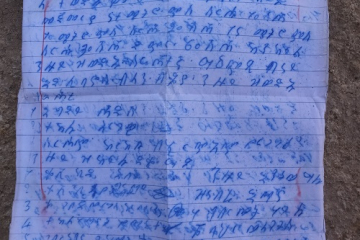

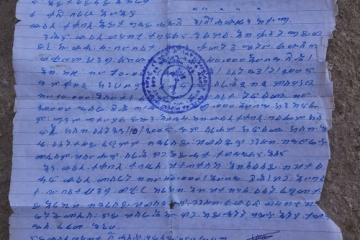

The administrator Ḥagos Gäbrä Ǝgziᵓabəḥer’s experience was enough, however, for him to be able to supervise the continuation of the project in the absence of either master craftsman. One or other, or both, would be called upon for advice and guidance when it came to doing such intricate work as carving arches and modeling pillars. According to the original contracts [Fig.10], each of the two Gidäys would be paid 40,000 birr to chisel out four square metres. Part of the money was raised by selling eucalyptus wood.

Gidäy Yəheyyəs is the son of a wood carver and it was from his father that he learned carving. “As I trained in wood, I carve the rock as though it were wood,” he said. It was his mother, wäyzäro Teberih [Täbarək] Assäffa, who as a nun brought him to his first site some twenty years previously.

Two at least of the four sites credited to him preexisted as small, presumably pre-sixteenth-century rock churches which he was invited to expand. Like Gidäy Hadush, he had no previous experience in rock carving, nor did he know anybody who did. His first church, at Harägᵂa Mikaᶜel (wäräda Ḥawzen, tabia Frewäyni, kushet: Harägᵂa) [Fig.11], was his training ground. A rock slide had demolished the north wall of the church, taking with it all but one panel of a fifteenth-century mural painting. With the north aisle now constructed of stone and covered with wood, Gidäy

Yəheyyəs carved out a south aisle and a new sanctuary at its east end [Fig.12]. His handiwork can be seen in well conceived arches, slender pillars, and a shallow cupola over the sanctuary [Fig.13].

His second church, at Maryam Mägdälawit, is also an expansion, this time of a tiny pre-existing rock-hewn site in which only the sanctuary was carved out of the rock [Fig.14]. The rest of the church, by contrast, was built and richly decorated with twentieth-century murals painted on cotton. The new excavation [Fig.15], by way of comparison, is an enormous cavernous undertaking modeled after the nearby church located considerably higher up in this part of the Gärᶜalta range, called Ǝnda Arbaᶜətu Ǝnsəsa [Fig.16.]. Ǝnda Arbaᶜətu Ǝnsəsa overlooks the outcrop of Gᵂəḥ at the western edge of the range. Its pillars are large and for the most part unremarkable, and it is arched. For Gidäy Yəheyyəs to copy its form was therefore not difficult, but the size is proving to be a major challenge and a considerable amount of work remains to be done.

The third church, Ǝnda Aba Gärima in the Səllaᶜ region of Gärᶜalta [Fig. 17], remains small compared to the others, but work is to continue once funds are secured. It is supported by a community of only 200 people. There was a church with the same dedication when I visited the area in 2006, but it was abandoned. The decision was made, very likely upon the advice of Gidäy Yəheyyəs, to change the location entirely and to move to another site where there was apparently a pre-existing rock-cut church. The church is currently circular in shape [Fig.18], but the plan is to extend it by another three metres into the rock on the north side, and to enlarge considerably the sanctuary [Fig.19], which at a present depth of only 1.5 m is barely large enough for the priest to perform the mass in. The pillars here are narrower and more refined than in Gidäy Yəheyyəs’ previous churches, a result of his having gained experience in the profession. His next project is to decorate the tops and bottoms of the pillars with crosses, enhanced by smaller crosses and stars around. The financing of the project remains in the hands of the priest, Ḫaylä Ṥəlasse Täsfaye, who already has raised 24,000 birr from the sale of hens, eggs, sheep, oxen and cows provided by the parishioners.

The fourth church, at May Wäyni Ǝnda Giyorgis, presents a major problem in that it is made up of three types of rock: red, white and black, and the black is harder and thus the most difficult to work with [Fig.20]. It is this harder rock which is slowing progress and making it more expensive, the consequence being that at the moment neither Gidäy Hadush nor Gidäy Yəheyyəs have been called back to work on it. Gidäy Yəheyyəs knows already, however, that because of the nature of the black rock, he will not be able to craft the ‘shapes’ he was able to achieve elsewhere. A related problem, which necessitates regular trips to the smithery [Fig.21], is that their tools break constantly as they attempt to chisel away at the hard rock.

What do these craftsmen know about rock-hewn churches that the architectural historians have not been able to determine? Today, the process begins with a meeting between the craftsman and the parish committee chosen to speak for the community as a whole. The negotiation will centre around the length, width and the shapes desired, and the way the interior is to be decorated. Once a written contract has been signed between the leader of the committee and the craftsman, work can begin almost immediately. The first step is to choose the right site [Fig.22], invariably one near a source of holy water, which in the case of an existing church to be enlarged is predetermined. Otherwise, the craftsman does a walkabout with the committee to determine which rock face would be the most desirable. Generally speaking, there should be no fissures and the rock should be soft enough to work. In the Gärᶜalta/Ḥawzen region, this would invariably be sandstone. While the final choice is usually left to the craftsman, who is best able to judge the quality of the rock, it is said that in the end it is God who determines the site. In the case of May Wäyni Ǝnda Giyorgis, the dedication is reported to have been established by six thousand angels.

The work itself is referred to as ‘chiseling’ and indeed the hammer and chisel are the primary tools [Fig.23]. Chisels come in various sizes, the most common being the steel reinforcement bars, or rebars, used to reinforce concrete. These are sharpened and regularly re-sharpened on a charcoal fire to which a constant supply of oxygen is introduced through the use of sheepskin bellows. The nature of the rock determines the type of chisel, as also the heavy hammer which strikes it [Fig.24]. In this manner, a day’s work is calculated to progress at an approximate vertical rate of one metre, and a horizontal rate of from twenty to fifty centimetres. Gidäy Hadush awaits the day when he can afford a jackhammer, but when that day comes, and it is not far away, the handicraft of making rock-hewn churches will disappear once and for all.

Ladders are seldom used as they are considered to be too dangerous; a workman can fall and injure himself. Instead, workmen are supported by the sand which they have dislodged either by working from the top down, or from the bottom up [Fig.25]. Wherever a church is being carved into the rock, sand is plentiful and can even identify a site from a distance, such as at Shewito on an outcrop in the plain northwest of Ḫawzen [Fig.26]. No sketch plan is necessarily made prior to the start of chiseling, although when the administrator of the church currently being chiseled at May Wäyni Ǝnda Giyorgis and craftsman Gidäy Hadush went to Gidäy’s birthplace in the near-by village of May Kado to see the rock-hewn Giyorgis church there [Fig.27], they made a drawing of the floor plan on a cotton sash to take away. May Kado Giyorgis is, in fact, the model for May Wäyni Ǝnda Giyorgis.

Once on site, charcoal is used as a means of indicating guidelines on the rock itself. For measurements, the standard fallback is the hand and the distance from finger to elbow, or a metre-length stick; some craftsmen admit the use of a measuring tape, but for the most part distance is determined by the workman’s eye. The same goes for the fashioning of decorative elements, such as arches and the capitals and bases of pillars [Fig.28]. The size of the pillar, that is whether it is slender or thick, is governed by its height and by the mass of rock above it; thus, the higher the pillar and the greater the mass, the thicker the pillar will be. Gidäy Hadush reported that if the rock is soft, he would place pillars no more than 2.5 to 3 m. apart.

To the question, “Which is better, a built church or a rock-hewn church?” the answer was universally “the rock-hewn church.” Why? Because it will last for hundreds of years without the need for upkeep and can thus be transferred from generation to generation. There was some disagreement about the cost differential, but the general consensus was that the rock-hewn church was cheaper because there was no need to purchase any building materials such as wood, stone, cement and corrugated iron for the roof. Considerations such as cost, durability and the lack of the need for building supplies and architects may also explain why, historically, there are so many rock-hewn churches to be found in the Gärᶜalta region and around the Ḥawzen Plain: it was simply cheaper to make them and building materials were hard to come by. The argument might be made that built churches in the region have disappeared due to exposure to the elements, but unless archaeological evidence for their former presence is found, it may equally well be that they never existed, or that if they did their numbers would not have been as great as one might think. The rock-hewn church was the obvious solution for a community of modest means to meet its spiritual needs for a place of communal prayer.

In view of the current tendency to expand pre-existing rock churches, there is another point which deserves our attention: the importance of recognizing that those examples which have survived from the past, especially the large ones such as Ṣəraᶜ Abrəha wä-Aṣbəḥa [Fig.29], Wəqro Qirqos and Mikaᵓel Amba (Wämbärta, Kələttä Awləᶜalo, Təgray), in all likelihood were originally conceived as smaller excavations than what we see today. There is every probability that they began as continuations of ancient places of worship which grew according to the needs of the local community, or with the more extensive means which could only be provided by a significant patron. While many of the rock churches in the Gärᶜalta and Ḥawzen regions can be attributed to foundations by, or in honour of, thirteenth through fifteenth-century saints, no secure chronology has been established for their introduction to the region, not to mention to highland Ethiopia as a whole. It has been argued that the three large churches just mentioned may, in their extensive cross-in-square format, date from as early as the eighth to tenth centuries. The presence, however, of an opening high up on the north wall of Lalibäla Mädḫane ᶜAläm leading to “two dome-shaped chambers” [Fig.30] provides material evidence that the site was used, ostensibly as a place of burial, prior to its transformation into a monumental phase. The fact that the side rooms which flank the sanctuary at Mikaᵓel Amba (Wämbärta, Kələttä Awləᶜalo, Təgray) were once open to the body of the church [Fig.31], a liturgical arrangement to extend the sanctuary adopted from Coptic precedents probably not earlier than the twelfth century and found at Lalibäla Däbrä Sina in the late fourteenth or fifteenth century [Fig.32], underlines the probability that the church as we know it today is not as it was when documentary testimony points to a foundation in the twelfth century. These examples, together with the contemporary enlargement of some of the ancient churches of the Gärᶜalta region described here, serve as significant reminders that while rock-cut architecture may well endure for a thousand years and more, the initial excavation was likely far more modest than what we know today. It is the current activity of those involved in chiseling churches into the rock that confirms this conclusion. [FIG.33] To understand the past, we must first recognize what is being accomplished before our very eyes, which may also serve as evidence that what we have always thought to be pre-sixteenth-century churches may in fact have been carved from the rock as a continuation in more recent centuries of an ancient tradition.

Notes

1. This is Halefon Teka according to David W. Phillipson, Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, Fourth-Fourteenth Centuries, New Haven – London, 2009, 121, Fig. 185 (see below).

2. Paul B. Henze, “Three New Rock-Hewn Churches,” prepared in June 1997 for the proceedings of the Third International Art Conference, held in Addis Ababa in 1993 (as indicated in his note no. 3). The editorship was assumed by Rita Pankhurst and was to be published by Red Sea Press, but the publisher left it in limbo and it unfortunately never appeared.

3. Pp. 2-4 of Henze’s notes. A third typescript, entitled “The Heart of Old Shoa,” and described as “Excerpts from a paper been [sic] prepared to accompany an illustrated lecture presented to the annual conference of Orbis Aethiopicus in Munich, October 1999,” contains much of the same information about these same new rock churches.

4. Henze gives the name as Halefrom Retta

5. Christine Chaillot, The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Tradition, p. 102. I am grateful to Fr. Emmanuel Fritsch for bringing this reference to my attention in an email dated 17 March 2015.

6. Phillipson, Ancient Churches, p. 121 and figs. 185 and 186.

7. Phillipson, Ancient Churches, p. 121.

8. Email correspondence dated 20 January 2014.

9. Email correspondence dated 8 March 2014.

10. The contract is dated 21-12-2002 EC, or 27 August 2010 Gregorian.

11. The contract is dated 23-07-2005 EC or 1 April 2013 Gregorian.

12. Ruth Plant, Architecture of the Tigre, Ethiopia, Worcester, 1985, no. 21, p. 66.

13. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, Wiesbaden, 5 vols., 2003 – 2014, vol. 2: 699b; Niall Finneran, et al., “Gärᶜalta,” EAE 2: 698a; Plant, Architecture of the Tigre, no. 18, p. 63.

14. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Gᵂəḥ,” EAE 2: 940-941.

15. Niall Finneran, et al., “Gärᶜalta,” EAE 2: 698a

16. Michael Gervers and Emmanuel Fritsch, “Rock-hewn churches and churches-in-caves,” EAE 4: 404a; Emmanuel Fritsch, “Tabot: Mänbärä tabot,” ibid.: 805b-806a.

17. Interview, 14 February 2015.

18. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Ṣəraᶜ Abrəha wä-Aṣbəḥa,” EAE 4: 628-630.

19. Wolbert Smidt, “Dängolo,” EAE 2: 87a – 88b.

20. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Mikaᵓel Amba,” EAE 3: 959-961.

21. Phillipson, Ancient Churches, p. 185b.

22. François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymer, et al., “Rock-cut stratigraphy: sequencing the Lalibela churches,” Antiquity 84 (2010): 1135-1150 (here p. 1138 and Fig. 3).

23. Fauvelle-Aymer, “Rock-cut stratigraphy.”

24. Emmanuel Fritsch and Michael Gervers, “Pastophoria and Altars: Interaction in Ethiopian Liturgy and Church Architecture,” Aethiopica 10 (2007), 7-51.

25. Balicka-Witakowska, “Mikaᵓel Amba, » EAE, 3: 960b.

Figures

(Please click to enlarge)