Digital Post by Ally_EdwardSaid

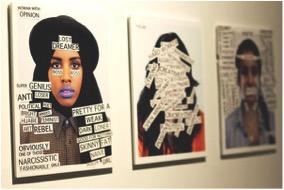

Image by Riya Jama from the article “Art show takes on the misrepresentation of Muslim” in ‘The Conversation’ (2018).

De Jager et al. (2017) explain that digital storytelling (DST) practices are often underfunded as there is an expectation to conform to traditional research formats. This is unfortunate, as DST holds much promise for countering dominant ways of knowing. I argue that while traditional research methods in biomedicine (such as Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)) have the potential to dehumanize the ill-person by focusing exclusively on the body as the origin of disease, by contrast, arts-based approaches, particularly DST, have the potential to remedy such effects by emphasizing the illness experience of a person (rather than focusing exclusively on a disease model).

Traditional biomedical research methods create an explicit distinction between the researcher and his or her “subjects.” By contrast, De Jager et al. argue that arts-based research approaches, such as DST, reduce power hierarchies between researchers and those with whom they work. The authors term it a “respectful, participatory research” tool. This is because those who participate in DST are able to influence the direction of the research in terms of topic, design and outcomes. Their knowledge and stories are valued and made part of the research process, making DST both an inclusive and valuable method when working with marginalized groups.

According to De Jager et al., conventional health research methods have historically involved an outsider studying and forming opinions regarding a certain group. The insiders themselves did not have an opportunity to create self-representations. However, through digital storytelling, individuals, particularly marginalized and stereotyped groups, are able to create their own narratives. Many of those involved in such arts-based projects mention feeling “empowered or liberated” after being able to share their stories and “take something that is hiding inside…and put it outside”.

Moreover, DST is a method that is easily accessible to the general population as one does not need to possess a certain level of expertise, literacy or academic skill in order to produce or understand a digital story. Farah Kabeer, a university student, published a blog entitled “Too Depressed to Go To Class Today,” in which she highlights her experience with depression and the impact it had on the course of her studies. Sensory elements, such as music and visuals, involved in DST allow individuals to share intricate and intimate details of their lived experiences that would otherwise not have been possible through writing (De Jager et al., 2017).By including an image which depicts a student falling and being trapped inside a black hole during class, Kabeer is able to powerfully capture feelings of hopelessness that many of those with depression experience.

While reading about the pathophysiology of depression in a medical journal , I was presented with a category of supposedly objectively, observable symptoms, including: lethargy, loss of motivation and interest in life, feelings of worthlessness and so on. Such an understanding of a complex illness, while reporting “correct” or commonly experienced symptoms, can also reduce one’s ability to sympathize with its sufferers, whom are depicted as patients first, rather than as holistic beings.

The arts and humanities offer us some alternatives when it comes to representing the complexity of health experience. For example, through her bold statement “I am Black, I am doctor, and I am here,” Chika Stacy Oriuwa reminds us of the intersecting aspects of our identities and invites the listener to acknowledge the diverse lived experiences of those around them. Not all of those who experience depression have the same illness story, nor will the causes and effects of their illness be similar. Biomedical research methods often disregard the diversity of our lived experiences. Individualsand their bodies are depicted as homogenous entities, leading to the assumption that every individual, with their different exposures to the social determinants of health, can all be treated in the same standardized manner.

Image from the article “Fragments of Mind-Body Dualism in Organ Transplantation” by Kristel Clayville (2016).

By contrast, through portraying the source of her depression as a result of social factors, Kabeer reminds us that our illness narratives are as diverse as our race, age, socio-economic status, gender and so on. Her inability to live up to Western beauty ideals (i.e. describing herself as ‘fat’ and ‘brown’) due to the intersecting factors of her identity (“a queer brown girl”) played an important role in her illness. Kabeer also discusses the role of immigration, including unfamiliarity with the culture and her “social awkwardness” as contributing factors to her ‘depression.’

Additionally, in a project involving DST, a group of refugees highlighted commonly held stereotypes about them. Refugees are commonly viewed as a single group, depicted as being worthless or a burden on their host society. However, through DST, these individuals were able to challenge dominant beliefs by creating “counter narratives”, as De Jager et al. describe. They were also able to illustrate that the ways in which we view certain topics or groups directly impacts our actions. If refugees are continuously represented as less than human, then our response would be to build larger walls, rather than bigger tables in order to shield them off. Therefore, the importance of creating counter stories and challenging dominant ways knowing the Other cannot be overstated.

Digital storytelling also helps us develop listening skills and learning about the experiences of others enables us to connect more deeply with them. The motto for StoryCenter.org, the home of digital storytelling, is: “When we listen deeply, and tell stories, we build a just and healthy world” (Lambert & Atchley, 2017). Storytelling sheds light on the many factors, such as our identities and environmental exposures, that are outside of our individual control and, which significantly impact the ways in which we experience well-being and disease.

Chika Stacy Oriuwa illustrates that one can simultaneously be “doctor, black and woman.” Similarly, just because an individual is a patient, does not mean that they cannot also be a mother, teacher, writer or simply a person. DST has the power to communicate the complexities of the illness experience. The biological and the social are never separate, neither are the mind and body. The methods employed by health humanities has the power to artistically and creatively conceptualize such health, suffering and illness-related concepts.