Post by HLTD50 student hhhipster

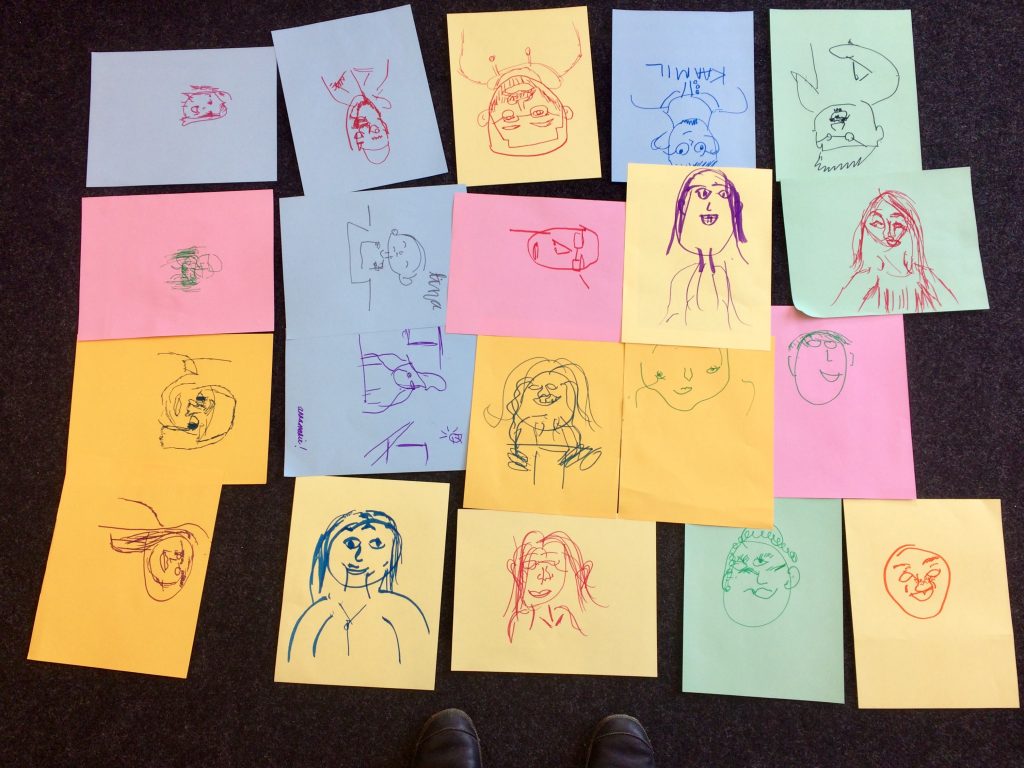

In our first meeting for HLTD50, near the end of the seminar Professor Charise got us to participate in an activity that involved forming random pairs. Once in a pair, we were tasked with drawing our partner’s face within a given time limit (a couple of minutes), without looking down at the paper, and to keep eye contact with our partners. After the activity was done, the pictures were placed side by side on the floor (The drawings can be seen below and on the main page of our blog!).

After having a brief discussion about how we felt about the activity, we were given the writing prompt: What did it feel like to draw your partner’s face?

My initial response was focused on eye contact and how it was uncomfortable to keep eye contact with someone I wasn’t particularly close too. Thoughts like this, in addition to brief connections with vulnerability and empathy were also listed but not explored thoroughly until I sat down to think about what to write for this blog post.

As I began thinking of ways to connect eye contact and health in relation to the class activity, I started to compare the different meanings associated with eye contact within the contexts of the class activity and healthcare and, surprisingly, in the context of music performances (where I have my own experience).

This lead me to consider reflecting and comparing the multiple meanings of eye contact has within different contexts, specifically: the class activity and performance settings into relation to healthcare settings. In all three contexts, eye contact as an act of intimacy and as a form of non-verbal communication are apparent. This eventually lead me to also reflect on how understanding the multiplicity of meanings associated with eye contact in these arts and humanities contexts could be used to add to our understanding of eye contact within healthcare settings.

Eye contact as an act of intimacy

- Class Activity: In this context eye contact was associated with “awkwardness” and being “too intimate” of an act to share with someone you did not know well enough. For the activity, drawing someone required being mutually vulnerable, which is an intimidating state to be in, especially if you did not know the person you were drawing particularly well. Being vulnerable in this case meant exposing one’s self to another individual and expecting the same of your partner: an implicit act of intimacy.

- In Performance Settings: In this context, eye contact is seen more as a subtle tool for musicians to communicate with each other, the conductor and even the audience. In contrast to the class activity, eye contact is less of an intimate act between musicians, but becomes intimate when it is between musician/performer(s) and audience. To be vulnerable in this context is a state in which musicians become because of willingly being on the receiving end of a one-sided gaze; of becoming a spectacle.

- Healthcare Settings: In contrast to the discomfort felt during the class activity of needing to make eye contact with another person, eye contact within clinical settings (i.e., doctor-patient interactions) tend to be an act of disenchanted formality that is usually one sided, which reminded me of the notion of the medical gaze from HLTB50 (Introduction to Health Humanities). Unlike performance settings where a musician willingly becomes a spectacle, in the healthcare setting those with disabilities or illnesses that are not easily curable may be subjected to becoming an unwilling spectacle. Vulnerability in this case becomes normalized and expected when in the position of the patient.

Eye contact as a form of non-verbal communication

- Class Activity: In this context lack of eye contact or an avoidance of eye contact allowed for people to take in other details of the person in front of them; their clothing, their surroundings, etc. Meaning the lack of eye contact allowed for a one-sided gaze to be used as a tool of observation. Even when eye contact did occur, avoidance right after was indicative of avoiding letting your emotions of unease or discomfort be conveyed to your partner.

- In Performance Settings: In this context, eye contact is used as a means of communication between musicians; between musicians in small ensemble groups, between a conductor and their orchestra or band in a large setting, etc. Unrelated to eye contact, musicians learn how to use methods of subtle non-verbal communication (“embodied knowledge” like physical gestures, breathing, etc.) to cue or signal between each other without affecting the performance of a piece. In that sense eye contact might be thought of as more of a purpose-driven act of communication.

- In Healthcare Settings: In contrast to a performance setting and to oppose the notion of the disenchanted interaction between a doctor and patient, would be the use of eye contact to convey or communicate empathy towards a patient. Unlike the class activity, eye contact can be a way for a doctor to judge a patient’s mental state when communicating their diagnosis to the patient; or even, perhaps, an index of paternalism towards a patient.

By comparing the ways in which eye contact is nuanced differently within the humanities, the performing arts and healthcare, we can begin to see ways in which we can work towards re-enchanting the experience of health and illness: one of the goals, according to scholars like Arthur Frank, of health humanities.