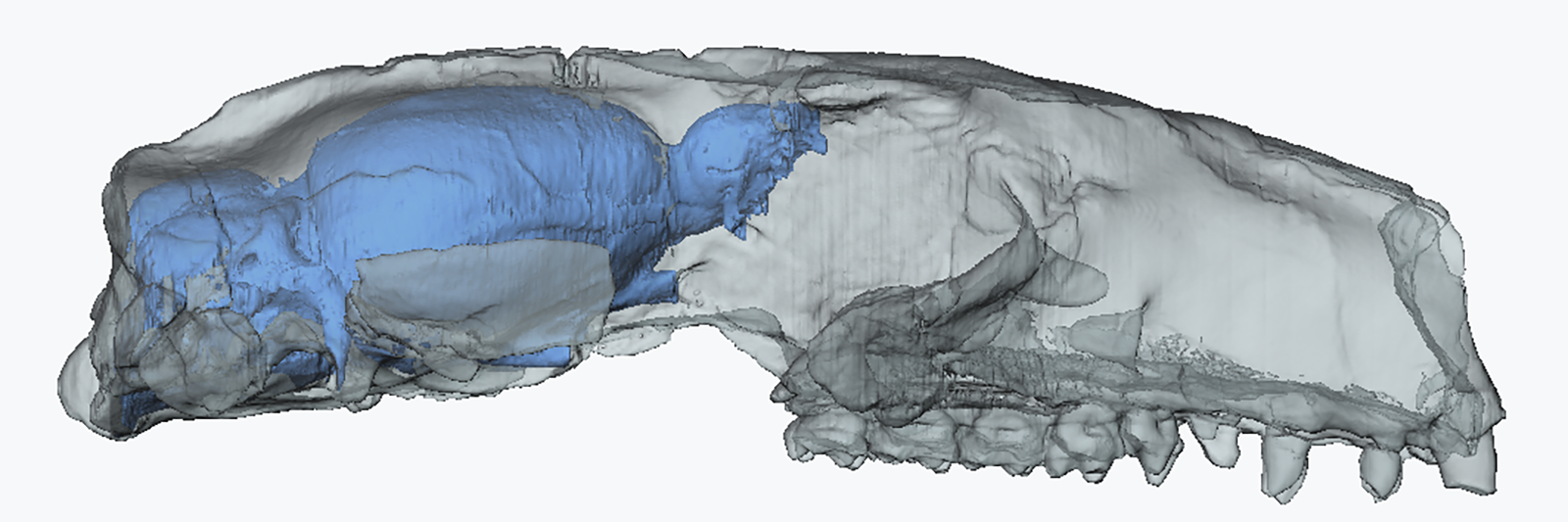

Pictured: CT image of plesiadapiform cranium, with the brain cavity highlighted in blue.

Building powerful brains requires access to high-energy food, making changing diet central to primate evolution. But studying the brains of early primates and how diet shaped them isn’t easy, because brains don’t fossilize. As a result, studies are limited to reconstructing the brains of our earliest ancestors from their living descendants. However, a UTSC vertebrate paleontologist has recently netted federal funding for a project that aims to use new methods to tackle the problem.

Professor Mary Silcox recently received a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to undertake a study to amass a dataset that will explore how shifting diets are aligned (or not) with changes in brain size and shape, using a phylogenetic framework that incorporates both fossil and extant members of Primates, and of closely related groups.

The study will examine fossils dating from between 65-45 million years ago, in particular the plesiadapiforms, a group of squirrel-like stem primates that lived in the Paleocene and Eocene epochs of the Paleogene period.

The study will use a number of innovative new technologies to expand our understanding of both the teeth and the brains of early primates. By using cutting edge dental topographic methods to allow for precise examination of the specific forms of primate teeth, the study aims to provide insights into lineages of early primates which have seen little quantitative study in regards to diet, due to them having patterns of adaptations not comparable with any living ancestors. The study will also use geometric morphometric and DiceCT methods to expand the information about changing shape and function that can be extracted from endocasts (the imprint of the brain preserved on the internal surface of the skull)

“Researchers have long been obsessed with how we humans got our big brains,” says Prof. Silcox “But it has become increasingly clear that just focusing on size gives us a very limited perspective on the evolution of the brain. It’s also critical that we put human brains into the broader context of primate evolution. This study will help build some tools that allow us to focus on more than just “bigness”, and try to provide some of that broader evolutionary context.”

For more information contact David Blackwood, Research Communications Coordinator, Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto Scarborough at David.blackwood@utoronto.ca

Illustration: Microsyops latidens by Ann Sanderson.