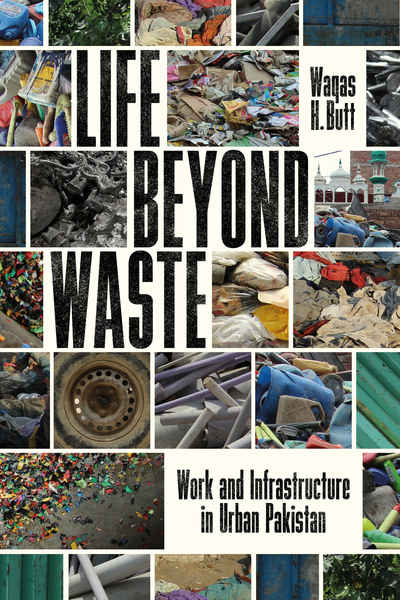

A new book by UTSC Assistant Professor Waqas Butt examines the rapid urbanization and socioeconomic transitions overtaking the city of Lahore in Pakistan through the lens of its marginalized waste workers.

Prof. Butt originally began his fieldwork into Christian communities in Lahore, a community to which many Dalits (noncaste) people belong. He found himself drawn into questions around the uneven urbanization of the city, and how caste, class, and religion have become embedded in urban life. For instance, waste workers in Pakistan come almost exclusively from low or noncaste groups.

Life Beyond Waste: Work and Infrastructure in Urban Pakistan is an ethnographical and historical study of how waste work has been central to the urbanization of Lahore – and how it is still inextricably linked with questions of caste.

“I’m looking at what is waste labor, and what does it do for a city like Lahore?” said Prof. Butt. “And within the question of waste work and urban life, I started to think around questions of caste. Who does waste work? Why are some parts of the city cleaner than others? Why do these caste dynamics continue to play out through this kind of labor?”

Dalit groups, formerly known as “untouchables,” are people considered of lower caste backgrounds, and have been employed in work traditionally thought of as unclean. They experience a great deal of discrimination across India and Pakistan even into modern times.

Prof. Butt spent time with sanitation workers in the recently-privatized municipal waste management system, forming relationships with the workers and joining them on their daily activities.

The history of municipal waste work and Christianity stretches into the colonial period when the bureaucratization of the existing structures of waste removal had that the side-effect of entrenching Dalit workers’ place in the waste industry. Colonial-era conversions of Dalit waste workers to Christianity added to the group’s marginalization.

“This situation reproduces caste, but in a transformative way where it's almost partly erased,” says Prof. Butt. “Because you say, well, this is a bureaucratic thing, right? It's not about caste discrimination.”

“People can recognize caste as playing out amongst Christian communities,” adds Prof. Butt, “But there's this sense that it's not caste in the traditional sense, because caste isn't part of Christianity. This attachment of caste to Hinduism allows it to be denied by other communities like Christians or Muslims, and in turn everyday social discrimination is erased. There is still a huge amount of discrimination around questions of like sharing food or marriage, where caste across religious groups and within religious groups continues to play out.”

Prof. Butt’s work also looks at the informal sector, in which both Muslim and Christian waste workers collect waste from households with which have created informal relationships. These private individuals and organizations make money from collection and sorting of plastics for recycling. Often these workers live and work in precarious settlements and bring the waste back to their homes to sort materials for them to sell forward. But the informal nature of their work means that their homes and livelihoods are inherently insecure and these settlements can be cleared at any moment.

“You can see how global economic trends affect people locally,” says Prof. Butt. He points out that fluctuations in the oil markets affect the price of plastics, and can have knock-on effects for waste workers and traders in Pakistan. The volatile circumstances of an economy based on consumption, disposability and the import and export of waste materials continue to enforce the stratification of caste.