Nowruz Table. Picture by Author.

Iranian immigrants, fleeing the Revolution of 1979, carried with them ritual New Year feasts along with the ancient Zoroastrian ritual of jumping over bonfires. Now in Toronto, Nowruz has become a large, at times even commercial enterprise similar to other holidays.

Rojina Samifanni, University of Toronto at Scarborough

Nowruz, the Persian New Year, marks the spring equinox and the equality of day and night on the 1stof Farvardin in the Iranian calendar, which fell on March 20 this year. The ritual celebrates the rebirth of vegetation with spring and the ability of people to provide food for their families. Persian immigrants have preserved Nowruz traditions in Toronto, although many rituals have been commercialized to fit busy lifestyles. Regardless, I still love preparing the ritual foods and celebrating Nowruz by visiting family and friends rather than the Gala events with music and dancing, featuring famous DJs and Persian singers, with ticket prices to match.

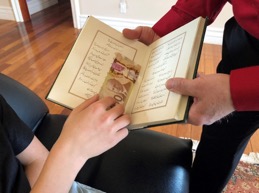

Reading. Picture by Author.

More than 2,000 years ago in ancient Persepolis, capital of the Persian Empire, Zoroastrians observed Nowruz by building fires on rooftops so that their ancestors would be able to find their way home. These fires were accompanied by seven plates of food as offerings called haft sini. With the coming of Islam in the eighth century, the original Zoroastrian symbolism of elements on the Nowruz table was replaced by new items: sumac evoking the sunrise, sprouts marking rebirth and renewal, goldfish for life, dried oleaster fruit symbolizing love, apples giving health and beauty, garlic for warding off bad omens, germinated wheat pudding demonstrating wealth, and vinegar pungently denoting age and patience. These offerings were placed alongside a candle or oil lamp, a survival of Zoroastrian symbolism that now represents goodness and honesty. There are also mirrors as a representation of God, painted eggs as a symbol of fertility, Persian coins (sekkeh) evoking wealth and prosperity, and purple hyacinth heralding the coming of spring. Originally placed on the floor, as a mark of humility, the offerings are generally set on a table covered by a pure white cloth to represent purity. When the New Year passes, each family member receives silver and gold coins, although today instead of coins, fresh crisp bills are given to children. It is also tradition to “sweeten the new year” by having Persian dry pastries set on the table.

Dry Pastries. Picture by Author.

Although the celebration lasts for thirteen days, originally three weeks, a high point takes place on “Red Wednesday” (Chaharshanbe suri) the week before the New Year, with fire ceremonies and symbolic foods as a ritual cleansing of the house and the spirit. Traditionally we eat ajeele chaharshanbe suri, which is a mixture of pistachios, apricots, and other dried fruits and nuts, along with a bean and noodle soup called ash-e-reshteh.

Perhaps the tradition that has persisted most over the years and across the diaspora from Iran to Toronto is growing barley and lentil sprouts before the New Year

Ash-e-reshteh. Picture by Author.

With the sizeable growth of Toronto’s Persian community over the past decade, these festivals have moved into the public sphere by filling venues like the Richmond Green Sports Centre, which featured performers on outdoor and indoor stages in addition to the fire jumping ritual. After several years of staying home, I went this year, and the crowd was unbelievable, with one long line up of people waiting to jump over the fire and another for the food truck serving the traditional ashe-reshte; both the fire and the bean and noodle soup helped to ward off the cold. Of course, some families still build small bonfires in their backyards and prepare ash-e-reshteh at home in a bid to avoid the crowds and preserve the intimacy of the holiday.[i]

Fire Jumping. Picture by Author.

During the course of the festival, the Richmond Green Sports Complex hosts a thriving market of Iranian migrant vendors who prepare and sell goods for Nowruz, including pastries and dried fruits as well as flowers, rugs, and home essentials, while real estate agents and mortgage loan businesses take advantage of the assembled crowd and hand out flyers and advertisements. Much of the dried fruit sold by the vendors is imported directly from Iran and can only be found at this time of the year such that their rarity is part the attraction. Vendors also sell the sprouts, made by soaking lentils and barley, which are essential to the Nowruz festival, but which can be difficult to grow at home. The evening bazaars are packed and moving about requires opportunistically darting through spaces in the crowd or better yet resigning to the glacial flow of densely packed revelers. Nor is it any less lively at other Persian bazaars around the GTA in Thornhill, Richmond Hill, Mississauga, and downtown. For their part, Restaurants indulge their customers’ taste for Persian folklore; around the end of New Year, the owners of The Pomegranate restaurant in downtown Toronto hire a storyteller to regale families as they eat their food.

Banquet at the Pomegranate. Picture by Author.

In my family, we take pride in our Nowruz dishes of sabzi polo mahi (rice and herbs with white fish) and kokou sabzi (fried herbs with egg), although we don’t make the equally traditional reshteh polo (rice with noodles and lamb) much less the dolmeh barg (stuffed grape leaves). White fish back home was caught fresh from the Caspian Sea, but here we usually get it from Asian supermarkets. This job is left to my dad, as he is the best at picking a good fish; my mom fries it with a coating of flour, paprika, and salt, which is not especially in keeping with tradition. We wash and boil the rice, line a pan with a little oil and pita bread, layer rice and herbs on top, and steam it over a low stove to incorporate the herbal flavoring into the dish. For the kokou sabzi, Persian Supermarkets such as Super Khorak at Yonge and Steeles supply home cooks with pre-chopped and packaged herbs, such is the labour intensive nature of the dish. In my family, we enjoy chopping the fresh herbs, adding my mom’s distinctive touch of walnuts and barberries, and frying the mixture with eggs. Reshteh polo, which represents success in life, uses a specific kind of noodles that are very chalky when uncooked and found exclusively in Persian supermarkets. (Personally, myself and my family exclude this dish from our New Year’s feast.) Dolmeh barg, which symbolizes the fulfilment of hopes and dreams, is extremely labour intensive, and I would doubt that many in Toronto would take the time to prepare it from scratch. We were fortunate for my grandmother who made an enormous batch when she stayed with us last, but the last of our frozen reserves have since run out; we hope she visits again soon.

Perhaps the tradition that has persisted most over the years and across the diaspora from Iran to Toronto is growing barley and lentil sprouts before the New Year. Although some people buy them in the market, many others plant them in early March so that the sprouts grow tall and grass-like by the thirteenth and last day of the New Year celebrations, known as sizdeh bedar, when families take their sprouts and picnic baskets to a park with a flowing river. They spend the whole day outside in nature for it is a bad omen to stay inside the houses on this day. Before sunset, we knot the sprouts, make a wish, and toss them in the river. This year, sizdeh bedarfell on a Monday, so many Persians celebrated on Sunday instead. Going on a picnic, having a grill, and being able to spend the whole day outside with family and friends gives a relaxing and cleansing finish to the Nowruz celebration.

Nowruz has evolved in Toronto into a major public festival that brings out young, old, the pious and the more culturally inclined. DJs spin traditional songs treated with top-40 production while importers sell delicacies fresh from Iran to customers eager to indulge in seasonal treats – if not real estate investment opportunities. The different ways one can choose to celebrate Nowruz suggests that public feasts are shaped by and in turn shape other community celebrations, Toronto’s many public religious festivals perhaps unified most strongly by their commercial flourishes. Nevertheless, Nowruz itself has been evolving for millennia and the DJs and pre-packed herbs may be fondly remembered one day as but just one more mode in a long cherished rite of Persian life.

[i]Kristin Rushowy, “A Green New Year: Toronto Restaurateurs Celebrate Persian New Year,” Toronto Star, March 15, 2006, page D1.