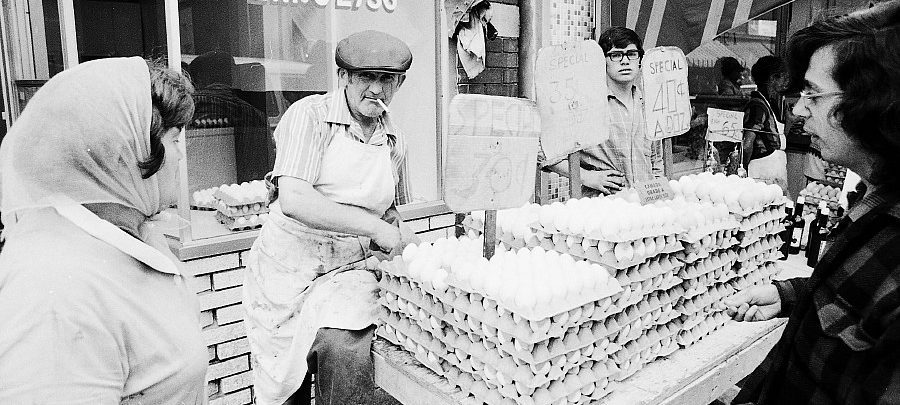

Torontonians have held no shortage of opinions about Kensington Market, located west of Spadina Avenue between College and Dundas streets. Alternatively described as a “breeding ground for vermin,”[1] a “mecca for all who value the rare, the unique and the exotic in this too-often unexciting life,”[2] and the “most humane property in the whole city,”[3] Kensington has meant very different things to its users since its informal founding around 1900.

Joel Dickau

University of Toronto

Today the Market is home to upscale dive bars and organic health food stores, yet vestiges of its storied past remain in the numerous small green grocers that still do a tidy business, or with stalwart shops like Carlo Periera’s spice shack that has been a hub for Portuguese newcomers and ambitious home cooks alike since 1971. In many ways, these small but tireless food sellers play the same role today that the Market’s live animal trade once did, encouraging Kensington’s current clientele to embrace the shambolic identity that has been cultivated and defended in its narrow streets for over a century.

In contrast to the St. Lawrence, St. Patrick and St. George markets, which were inaugurated by public decrees in the mid-nineteenth century, Kensington’s retail environment unfurled piecemeal, from the ground floors of a residential neighbourhood. Its major avenues were established by a handful of wealthy English families in the 1850s, but by 1900 had become home to Toronto’s expanding Jewish population.

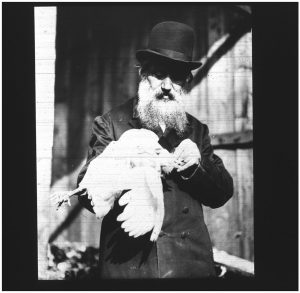

Man Holding Chicken, William James Slide 39.1. Courtesy of City of Toronto Archives.

Jewish women and men searching for the familiar tastes of Eastern Europe began to supply themselves – and whomever happened to wander into the Market’s loosely defined boundaries – with produce, eggs, rye bread, and with fresh poultry plucked from cages that could be carried to one of Kensington’s Shochets for kosher slaughter, most of whom also ran their businesses from inside their homes.

Sign in Yiddish advertising Chickens, William James Slide 39.4. Courtesy of City of Toronto Archives.

One of Toronto’s most prolific early photographers, William James, was fascinated by this trade and documented it in a series of photographs taken between 1910 and 1920 that captured the involvement of young, old, women and men. James’ intentions in documenting the Market remain private, however the live poultry trade along with the produce and homewares businesses that had by the 1930s taken over long stretches of sidewalk, drew the leering curiosity of the City’s majority Anglo public. One 1946 photograph appearing in the Toronto Star bore the following caption: “Orthodox Hebrews, of course, buy their fowls alive and have them koshered by a rabbi. This hen hasn’t long to live. It will be taken to one of the money rabbis whose headquarters are in alleyways off of the market streets. Kensington has much of New York and Chicago’s color.”[4]

Orthodox Hebrews. Toronto Star Photographic Archive, 0024367f. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

Entering the postwar period dreaming of ordered modernity, Toronto’s councillors saw the Market’s sprawling live animal trade as an anachronism. In 1947, council prohibited anyone from slaughtering fowl, storing poultry or operating a poultry market in an area that included Kensington. However, pressure from the neighbourhood’s Jewish as well as Italian and Portuguese butchers forced council to relent, which it did three years later by allowing a number of slaughterhouses and live animal sellers to persist, albeit in a highly regulated manner. And so, the clucking chickens, sniffling rabbits and fish swimming in large tubs remained a key part of the Market’s sensory environment into the 1980s.

“The incorporation of Kensington into the City’s awakening imaginary of progressive cosmopolitanism was a boon to many new shop owners, but weighed on the Market’s oldest business owners and clients, especially its live animal vendors.”

Kensington Market. 1964. By Ellis Wiley, Fonds 124, File 7, Item 4. Courtesy of City of Toronto Archives.

Kensington was by no means spared public intrusion, however. By the early 1960s, the Urban Renewal policies that had swept through Boston and New York were being employed with full force in Toronto. Plans to revitalize the city core with high rise rental buildings and expressways were scaled down for the Market. Its main business streets were to be paved with tile and demarcated for pedestrian use only, while produce vendors whose goods were typically crowded into makeshift cases beneath vibrant awnings were mandated to use steel-built stalls approved by the public health department. Planners hoped these measures would halt the spread of the Market into the surrounding residential streets, giving a physical boundary to the zoning permission they had finally granted to the existing business area.[5] Kensington’s business and residents’ associations managed to steer the project’s implementation so that a new parking structure was built to everyone’s satisfaction, while plans for the stalls and the pedestrian space languished amidst association infighting and to community resistance to urban renewal more generally throughout the City. As the months passed, the will to make fundamental changes to Kensington’s infrastructure waned. Yet even though the Market appeared much the same as always, it was evolving into a public site subject to a new order of public scrutiny.

Following the war, most of Kensington’s Jewish community moved northward along Bathurst Street. In their wake came Portuguese, Italian and Jamaican migrants who settled in and set up shops of their own. As the 1960s gave way to the 70s, its diverse user base was coming into a new light, valued in newspapers and development reports for its “old-world charm.”[6] Attracted to this charm were bohemians, counterculturalists, and Toronto’s draft-dodging expat community who hung around at Grossman’s Tavern, nearby.[7] Kensington native Al Waxman drew further attention to the neighbourhood with his CBC sitcom King of Kensington, which cast him as Larry King, a long-suffering variety store owner who reluctantly navigated the ethnic and social conflicts that the Market plausibly gave rise to. The incorporation of Kensington into the City’s awakening imaginary of progressive cosmopolitanism was a boon to many new shop owners, but weighed on the Market’s oldest business owners and clients, especially its live animal vendors.

Little had changed in the way chickens were kept in Kensington over the decades, and that was increasingly a problem. Throughout the 1970s, animal rights activists and the Toronto Humane Society – the City’s hired animal control agent – pressured lawmakers to once again ban the sale and slaughter of poultry and rabbits in the Market. Citing inhumane living conditions and the birds’ propensity for attracting rodents, Humane Society staff conducted clandestine inspections and on multiple occasions stripped vendors of their flocks. Public attitudes towards the vendors were mixed, but the controversy was nevertheless able to ensnare them in the City’s ongoing efforts to strengthen its general animal control policies. Along with stiffer fines for bad behaving dog owners, live chickens and rabbits were to be banished once and for all from the urban environment. Opposition to the proposed ban came strongest from specialty rabbit breeders and DIY urban farmers whose backyard roosts had been surprisingly left alone by Toronto lawmakers for over a century and a half.[8] As for the vendors, a weak defence was mounted in the mainstream press, but as one Italian language newspaper lamented, it appeared to be a foregone conclusion.[9] In June of 1983 the animal control act was passed and live chickens, rabbits and fish disappeared from the Market’s streets.

There remain a few shopkeepers today, including Carlo Periera, who remember when chickens patrolled Kensington’s alleyways. An anthropologist recently conducted several interviews for a book on collective memory making in Kensington, and asked Carlo about the animals. “The government has cleaned it up, which is a good thing, environment and health wise,” he said. “You have to do that, right? I think it is for the good.” She also spoke to Yvonne Grant, owner of Caribbean Corner on Baldwin which opened in 1977, who expressed a similar ambiguity. “Kensington Market was much different, much different. It had . . . it use to have live chickens, more smelly and the buildings were relatively more dilapidated.”[10] Perhaps these shopkeepers believe that the contemporary user base would not welcome live animal selling. Perhaps they welcome the shift towards a younger, wealthier Market crowd interested in restaurants, gluten-free bakeries and boutiques. Yet though the transformation has been significant, giving rise to new conflicts between global tourists and long-term residents, Kensington’s ragamuffin atmosphere persists. And it persists thanks to the handful of produce vendors and small food retailers whose crowded shops remain as purposefully chaotic as ever.

Notes

1 Letter from Edith Tressider to Mayor Saunders, February 8, 1946, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, Series 361, Subseries 1 Files 582-585.

2 “Miracle at Kensington,” report by Alderman Horace Brown, April 17, 1968, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1337, File 180.

3 “Expansion and the University,” The Varsity: Community Issue, November 28, 1969, p. 8.

4 Toronto Star. 1946, unknown photographer, Toronto Star Photo Archive, tspa_0024367f.

5 “Urban Renewal study, Kensington,” 1969, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 2032, Series 723, File 7.

6 “Why spoil Kensington Market?” Toronto Star, July 4, 1982, p. F2.

7 David Churchill, “American Expatriates and the Building of Alternative Social Space in Toronto, 1965-1977,” Urban History Review 44, no. 1 (2010): 39.

8 “Animal Control,” 1982-1983. City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 1306, Series 310, Subseries 1, File 86.

9 “Merchants cry foul over proposed ban on chickens,” Toronto Star, May 4, 1983, p. A6; “Maiali e pecorelle banditi da Toronto,” Corriere Canadese, July 13-14, 1983, p. 5.

10 Na Li, Kensington Market: Collective Memory, Public History and Toronto’s Urban Landscape (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), 64-65.