By Siera Vercillo- Postdoctoral Fellow, Feeding City SF3 Lab

Ten years ago, when I moved to northern Ghana for the year, my friends living just outside of Tamale, northern Ghana’s major urban centre, would often make fun of me for eating fried rice -served with mixed vegetables, scrambled egg and chicken or guinea fowl. They considered rice ‘light’ food that foreigners like myself ate. They compared this light food with the ‘heavy’ staple of TZ (Tuo Zaafi) which they preferred to eat every evening. Recently, those same friends asked me to bring them fried rice from a vendor in Tamale, or to a restaurant there serving pizza, a food they kept hearing about but had not yet tried.

Preparing TZ meal at home (served with soup and stewed vegetables, meats and fish) compared with a purchased rice dish from a local food vendor (served with fried meat, noodles and raw lettuce) in the city center of Tamale. June and July 2022

Since I first moved to northern Ghana, I have been revisiting to conduct participatory research with smallholder farming families in rural areas around Tamale. My latest research project is focused within the city itself where I engage with neighbourhood food producers, food vendors, and restaurants, as well as government, NGO, and association representatives about local food practices and how they relate to global food systems.

Based on my interactions with Tamale residents in the summer of 2022, I found two contradictory food trends that reflect some of my friends’ changing food interests. On the one hand, they had adapted to global food practices, like producing, selling, and consuming highly-processed ingredients and foods grown with heavy doses of inorganic fertilizer and agrochemicals. On the other hand, many people still maintained local practices, such as cultivating and selling staple ingredients grown nearby with minimal external technologies. This essay explores some of these diverging practices through narratives and photographs from Tamale.

Breakfast with a market vendor in the Tamale neighbourhood of Zogbeli. She serves an omelet fried with red pepper, onion, and bread. This ‘egg and bread’ is sometimes served alongside a locally grown black-eyed pea stew with shito sauce (fishy hot pepper sauce), imported Lipton tea, Nescafe, and Milo. May 2022.

Attending the regional Ministry of Food and Agriculture held pop-up market (supported by donors) which invited vendors promoting locally produced, processed and packaged food and other herbal remedies and skin/hair care products. June 2022

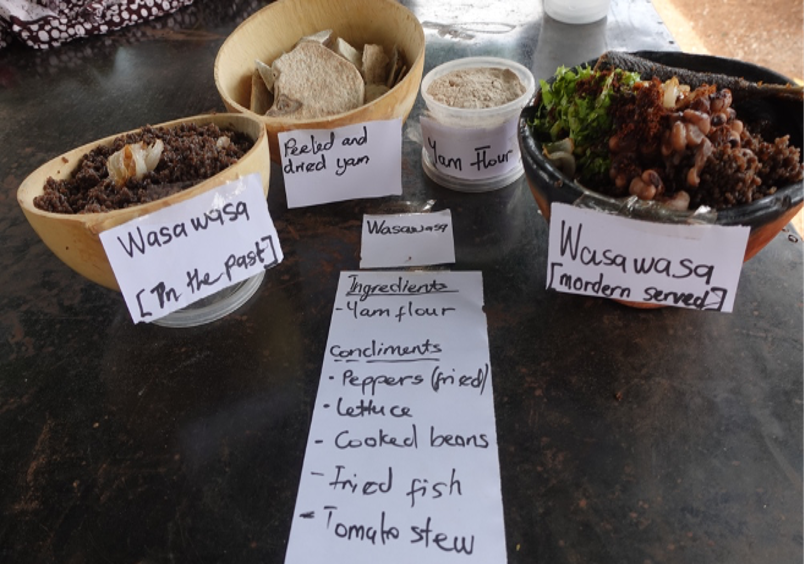

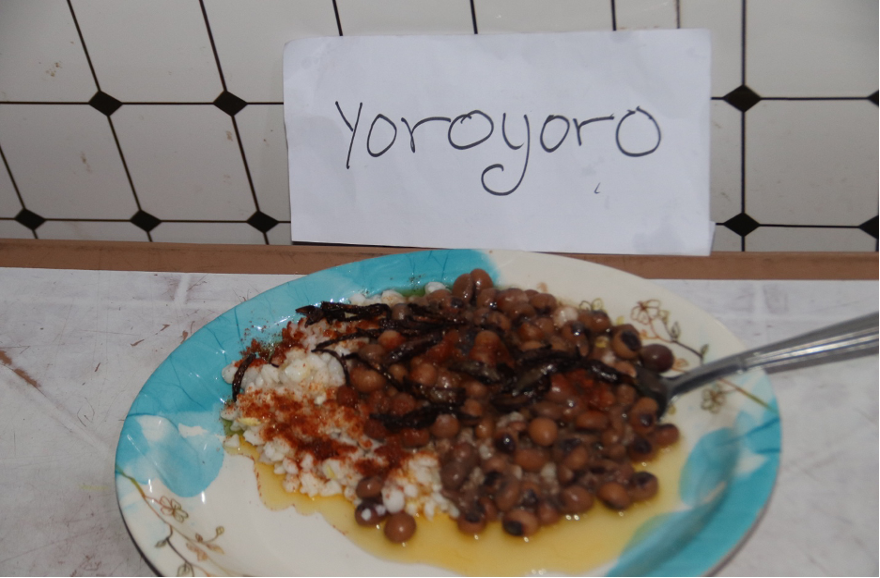

Below are some of the foods and ingredients that many Tamale residents described as ‘local’ or ‘traditional’ foods. Some people took the time to demonstrate how to process and prepare them. The next picture shows one of those foods – a soup of pounded locally grown greens and vegetables like alefu (amaranth), ayoyo (jute), and bean (black-eyed pea and/or cowpea) leaves, among others, cooked with hot peppers, tomatoes, onions, dawadawa, and typically stewed with smoked/salted fish like herring and mackerel, as well as goat, sheep, beef, among other salted meats. Saltpetre is also often added to enhance the texture and colour of the dish. This soup is served with the staple TZ (Tuo Zaafi) that my friends (among many others) referenced, which is a stirred or paddled maize/millet flour that a typical family in the north would eat at every evening meal. Below, there are also a series of short videos I filmed featuring Chef Amina in what she calls her indigenous food kitchen, Duduhgu Experience, which you can visit in Tamale to learn more about disappearing foods and underutilized traditional ingredients. Further pictured are many of the ‘disappearing’ foods that people described like nyombayka, tubani, gabli, wassa wassa, yamkahanda, yankale and yoroyo that are typical to the north of the country. Also pictured are ‘underutilized’ ingredients that people described like dawadawa and canton, which are locally foraged and grown fermented flavourings.

Making green green soup that can be served with TZ (Tuo Zaafi) in culinary demonstration videos. July 2022

These are videos of Chef Amina in her Duduhgu Experience which features traditional or indigenous foods and ingredients in Tamale. In the first video, we prepare dawadawa jollof (steamed rice dish) which tastes like every rice dish I had eaten in rural communities across the northern regions. It is prepared with shea butter instead of imported oils, green onions (dried and crushed), dawadawa, ginger, onion, scotch bonnet pepper, tomatoes, smoked mackerel and herring, and parboiled rice instead of perfumed jasmine rice. In the second video, Amina describes the different types of rice used to prepare this dish among others.

Making nyombayka in a culinary demonstration video, prepared for Tamale’s market. July 2022

Preparing tubani and gabli with ingredient list in culinary demonstration videos. July 2022

Preparing wasawasa in culinary demonstration videos served with and without a dollop of shea butter (on the left) and smoked fish, stewed beans and salad (on the right) where it was described how the dish has changed over time. June and July 2022

Yamkahanda taught in culinary demonstration videos. July 2022

Yankakle prepared in culinary demonstration videos with ingredient list. July 2022.

Enjoying yoroyoro after a culinary demonstration. July 2022.

Canton spice (cotton seed), taken in culinary demonstration videos of disappearing ingredients. August 2022.

Dawadawa spice, taken in culinary demonstration videos. August 2022.

The Ghanaian research team and I had countless conversations with each other and with others about how people are increasingly eating foods influenced from outside Ghana, like (expensive) pizza and (cheap) instant noodles. Pizza in Ghana tastes like what you would get at a Pizza Hut in Canada, only with less tomato sauce and more cheese. One chef described Ghana’s pizza as a ‘zoo’ because they like to put all the animals on it -red meat, poultry, snails and so on. Some described pizza as a luxury food served at expensive restaurants where you may take someone out on a date. However, instant noodles was observed as a cheap, fast food eaten late at night at food stalls, where it was fried up with onion, green pepper and red meat for men coming back late from work or from the bar. Kids also took it with them to school for breakfast or lunch. The vast majority also cook these dishes, as well as local dishes with imported highly-processed ingredients like Frytol vegetable oil and instant spices like Maggi and Onga.

These global food practices represent the nutrition transition theory I study- that as local food economies industrialize and globalize, people begin to seek out more highly processed foods associated with a global diet. This change in food preference is thought to be a major cause of why there are staggering increases in non-communicable diseases globally, particularly across countries in the Global South. Ghana is a good example of this trend as obesity is highest in West Africa, having increased 2.5 times over the past ten years when the country moved from predominantly rural to urban, and from lower-income to middle-income country status.

But people’s choices to consume foreign, highly processed foods and ingredients are more complicated than personal preferences associated with urbanism and upward mobility. I learned there are several reasons for these dietary changes. Instant spices are cheaper, faster to use and sometimes more readily available in shops and stalls compared to locally produced and foraged flavourings like dawadawa, canton and smoked fish, especially during off season periods. Acutely erratic and less rainfall overall, shortening growing seasons, heat stress and aridity associated with a changing climate also make many locally produced and foraged staples and flavourings less available since they are predominantly rain-fed. And NGO, donor and government support for high-yielding monocrops like maize and rice in line with the Green Revolution that require huge amounts of inorganic fertilizer and agrochemicals also take up the land where many local staples like sorghum and millet, intercropped with other important ingredients were once grown.

Instant spices as examples of highly processed imported ingredients found in virtually every food stall and shop. June 2022.

An example of what people described as cheap ‘fast food’ – imported rice and beans (waakye) with a smoked fish and vegetable-based stew that I had difficulty eating because of the large amounts of instant spices included. The restaurant was also covered in the Chinese tomato paste company branding of ‘Tasty Tom’, which also has elaborate TV commercials advertising instant spice mixes used for cooking jollof. June 2022.

A typical cheap ‘fast food’ joint that was described as one of the fastest-growing businesses in the city. These claims are easy to believe given how many more of these types of food joints are observable in the city compared to five years ago. They typically advertise popular foreign foods like Coca-Cola products, ‘pure’ bottled water like what is pictured here to attract customers. July 2022.

Signboard advertising a KFC meal or what people described as expensive foreign food. This is growing in popularity as corporations flock to the growing number of consumers in ‘emerging’ urban African markets. KFC only opened in Tamale in 2018, originally with a drive-through. I found this exclusionary of one of the most popular modes of transport in the city, which are ‘yellow yellows’ or shared, open-aired, three-wheeled taxis (referred to as tuk-tuks or auto rickshaws in other places). June 2022.

As people develop a taste for highly processed spices and oils, and foreign foods that are high in salts, sugars and fats, they request and seek them out further. Many different kinds of people -rich and poor – old and young – educated and illiterate- described how they felt trapped in addictive cycles of taste. They are consuming less variety and more unhealthy ingredients. People described consuming fewer local ingredients as a crime against their cultural traditions and knowledge, which they fear will be underappreciated and lost with subsequent generations. For instance, one man in a focus group said,

‘We used to eat the cotton seed and dawadawa with TZ and we were healthy. But, now, there is Maggi. In the past, our great grandfathers were not eating Maggi.’ He claims, ‘Now, it has led to so many complications in terms of our health, causing waist pains and even stroke!’ He explains further that, ‘We have become used to it, and if it is not in soup, we will not feel like eating it. Even if you say you don’t want Maggi, your wife will hide and put it in the soup. So, we are stuck.’

Much like poverty, global food (imported or produced locally) is trapping many in a cycle of unhealthy and environmentally unsustainable eating. Some described how rich people are seeking out organically produced food and foraged local flavourings because they are perceived as healthier and safer to eat but are sometimes more expensive and difficult for the average person in the city to find compared to just 20 years ago.

To date, scholars theorize that as countries in the Global South urbanize and industrialize, as people produce commodity crops for export, people’s tastes and food preferences also orient towards global products that are served with and largely by multinational corporations and their products. My fieldwork is alternatively illustrating a different picture. In other words, people in Tamale consume global foods and ingredients in different ways and for different reasons that are sometimes out of their control, while others are better able to maintain local practices. These findings show new perspectives on existing nutrition transition theories of how and why people’s diets change in developing economies.

About the author: Siera Vercillo is a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Feeding City Lab who has been working with communities in Northern Ghana over the past 10 years.