By Jeffrey Liu, Junior Researcher

Introduction

It is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted the restaurant industry in Canada and abroad. Knowledge of how the pandemic has affected disparate types of food businesses is comparatively lacking. In this article, I summarize and reflect on my recent research project that explores how the pandemic has impacted Indian-Hakka restaurants in the Greater Toronto Area. I argue that the resiliency of Hakka businesses is partially rooted in their historical background as itinerant cultural minorities. The strategies that these businesses used to succeed in Canada prior to the pandemic and throughout it are a product of cultural adaptations made to meet the demands of cultural outsiders.

Methodology

My research is primarily informed by a survey I conducted with Indian-Hakka restaurant owners. Working within my own cultural community brings the benefits of easier access, legitimacy as an interviewer, and personal ethnographic insights. I also acknowledge that this positionality also invariably biases the data I collected.

Two participants were surveyed using a detailed online questionnaire. The first was Linda Huang, the co-owner of Golden Joy, a Indian-Hakka restaurant located in Etobicoke’s Thistletown neighborhood. The other respondent requested to be anonymously identified as a second-generation proprietor of a restaurant in Scarborough and thenceforth will be referred to under the pseudonym Daniel. Engaging with these restaurateurs reveals the nuanced ways that Hakka eateries outlasted the difficulties prompted by the pandemic. Given the limited sample size of my data collection, I have also consulted the limited media coverage available for the experiences of other Indian-Hakka restaurants in the GTA. I also frequently consulted The Hakka Cookbook, authored by Linda Lau Anusasananan, for information on the culinary elements of Hakka dishes, as well as for the author’s personal anecdotes and insights on Hakka culture. Opportunities for further scholarship include increasing the number and breadth of respondents and to include restaurant employees.

The Hakka Cookbook (2012), authored by Linda Lau Anusasananan, explores the culinary traditions of Hakka cooking, relating them to a history of diaspora, hardship, and oppression.

The Hakka Odyssey

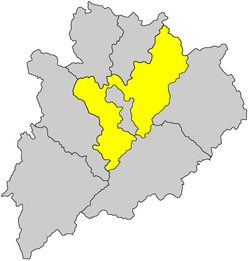

The Hakka people are an ethnolinguistic Han Chinese subgroup dispersed across China and the rest of the world. The majority of Hakkas trace their descent to the Meixian District in Guangdong Province in China (Lau Anusasananan 24). However, historians believe that the Hakka people originated in the Central Plains of Northern China, migrating south from the third century BCE onwards in response to social upheaval and famine (Chiu 12). Because of this, Hakkas are described by anthropologist G. William Skinner as the only Chinese subgroup with “no drainage basis of their own,” living as minorities in various southern Chinese provinces (Lau Anusasananan 22). Traditional Hakka food is characterized by a diverse blend of preserved foods due in large part to the Hakka’s history of migration (Chiu 111).

Meixian District (Highlighted) within Guangdong Province in Southern China

Denied access to prime agricultural lands in Guangdong and forced to live on inland hill regions, Hakkas were often persecuted and stigmatized as backwards barbarians due to their status as cultural minorities within the provinces they lived in (Chiu 11). Such factors led Hakka people to migrate in the latter half of the nineteenth century to places across the globe as disparate as Malaysia, Mauritius, Jamaica, and India — many worked as indentured workers in colonial societies (Lau Anusasananan 25). In my study, I focused on what became of the Hakkas that migrated to South Asia because this is the community I belong to and the region where I have the most cultural knowledge.

Many Chinese settlers came to India in the nineteenth century through the active trade that occurred between the ports of Calcutta and Canton/Guangzhou. Permanent migration intensified during the periods of civil strife that frequently occured in this era of Chinese history. Throughout India, Chinese migrants established their own neighbourhoods, schools, and community institutions, living fairly endogamously (Xing and Sen 214-216). The British administration estimated that by 1945 there were roughly 26,250 Chinese people permanently settled in India, the majority of whom were Hakka (Oxfeld 411).

Lion dance as apart of Lunar New Year festivities in Tangra, a district in East Kolkata that housed much of the city’s Hakka community as well as the tannery industry they supported.

In Calcutta, the city with the largest Chinese population, the Indian-Hakka community largely worked in shoemaking and by extension also in leather tanning in later decades (Xing and Sen 209). The tannery industry was concentrated in the outskirt neighbourhood of Tangra/Dhapa, which grew to become one of the city’s Chinatowns (Xing 399). Leatherwork was perceived as a low-caste activity in traditional Hindu thought (Oxfeld 418). In this sense, Indian-Hakkas filled an occupational niche carved out by Indian culture and customs and managed to make it highly lucrative.

Nevertheless, Chinese people living in India did not exist and operate in isolation. Indian-Hakkas learned to become conversant in the local languages through their interactions with South Asians in business and daily life (Oxfeld 424). Members of the community who grew up in more recent decades attended English or Hindi-medium schools, unlike their forebearers who primarily attended schools where Chinese (Hakka or Mandarin) was the language of instruction. Some of India’s Chinese even converted to Hinduism or at least partially adopted Hindu religious beliefs (Xing 406). Chinese food vendors and merchants also conducted business in multi-ethnic spaces like the Tiretti Bazar and cultural events from one group invariably drew onlookers from the other (Xing 411). My father, whose childhood memories harken back to the 1960s, grew up in the northern hill station of Ranikhet where his family were the only Chinese in town. He later moved to Calcutta in his youth and frequently speaks fondly of his memories participating in Holi festivities and shopping for Indian sweets at the local market. Thus, a great degree of intercultural exchange occurred.

Beginning in the 1970s, much of India’s Chinese community started to emigrate out of the country. The central factor motivating this exodus was the Indo-China War that occured in 1962. This war resulted in a wave of anti-Chinese xenophobia and legal measures that restricted the freedoms of Chinese people living in India (Xing 407, Xing and Sen 224). These factors, in combination with the decline of the tannery business — due to the emergence of competitors and new environmental regulations — motivated many Hakka Chinese living in India to look for opportunities abroad (Xing and Sen 209). Today, the largest community of Indian-Hakkas live in the Greater Toronto Area (Xing and Sen 224).

Indian-Hakka Cuisine

Chinese-owned restaurants existed in India as far back as the early twentieth century. It is under this cultural backdrop that Indian-Hakka cuisine developed. The British administrator Shelland Bradley wrote in 1924 about his experience visiting a Chinese restaurant in Calcutta. He noted that they served upscale traditional Chinese fare like bird’s nest soup but also hybridized dishes like “Chinese curry” (Xing 400). By the start of the Second World War, there were at least 150 Chinese restaurants operating in India (Xing 211).

Chilli Chicken, one of the most popular dishes at Golden Joy, is prepared using a blend of soy sauce, Indian chilli powders, and deep frying.

Indian-Hakka cuisine as it exists today is the product of intercultural synthesis that occured between Hakka cooks and demands and preferences of a predominantly Indian clientele. This was done through the blending of Indian spices with Chinese techniques like stir-frying and East Asian ingredients like soy sauce, resulting in a finished product that was neither traditionally Chinese or Indian (Lau Anusasananan 199).

Diet was one of the central markers of difference for Chinese people living in India. Chinese people were set apart by their consumption of beef and pork, meats that Hindus and Muslims respectively generally abstained from (Oxfeld 418). Therefore, by crafting a cuisine that attempted to meld these disparate elements, Hakka cooks were asserting their belonging within the cultural landscape of South Asia. Conversely, by patronizing these restaurants, Indians could partake in dishes that were familiar yet foreign, thereby experiencing “Chineseness” within a culturally and culinary safe space.

Indian-Hakka Restaurants and Intercultural Resilience

My interviews with Linda and Daniel reveal that the food they serve at their restaurants are not something they commonly ate growing up. Linda Huang, the middle-aged, first-generation co-owner of Golden Joy, an Indian-Hakka restaurant in Etobicoke, defined traditional Hakka food as dishes like “steamed tofu, salt baked chicken, [and] pork preserved with vegetables,” describing the cuisine served at her restaurant as a product of “our palate change; one that has integrated Indian spices … a product of our Hakka culture in India.” Indian-Hakka dishes like chili chicken or Manchurian chicken (which bears no resemblance to traditional Manchu cuisine) are a far cry from Linda Lau Anusasananan’s description of Hakka food as “salty and fatty.” (Lau Anusasananan 26)

Daniel, the second-generation owner of an Indian-Hakka restaurant in Scarborough, specifically listed Indian spices like curry powder, garam masala, and dhana jeera as central elements in the dishes offered by his restaurant. Both respondents report that their establishments served a bevy of halal and vegetarian options to cater to their customers. Therefore, Indian-Hakka cooking itself is a product of resilience — a cuisine created through filling a niche in a foreign cultural landscape in a way not dissimilar to the establishment of Hakka tanneries. Daniel argued that Indian-Hakka immigrants opened restaurants in Canada “since that is their strongest asset.” Both respondents come from families where their parents and other family members worked at and owned food businesses in India and abroad.

Golden Joy, owned and operated by Linda Huang and her family, is located in Etobicoke’s Thistletown Neighbourhood at the intersection of Islington Ave and Albion Rd (900 Albion Rd Unit 18, Etobicoke, ON M9V 1A5)

Golden Joy, owned and operated by Linda Huang and her family, is located in Etobicoke’s Thistletown Neighbourhood at the intersection of Islington Ave and Albion Rd (900 Albion Rd Unit 18, Etobicoke, ON M9V 1A5)

Hakka cooking tends to integrate foreign culinary elements and this is rooted in the history of Hakka peoples as itinerant cultural minorities. For example, Lau Anusasananan notes that ingredients like yuca and bonnet chile feature prominently in Hakka dishes from Peru and Jamaica respectively but are not found in Hakka cooking elsewhere (Lau Anusasananan 28).

Both of my respondents report a decline in revenue and the necessity of having to lay off some employees and cut hours for the rest. Prior to the pandemic, 40-50% of their revenue was derived from dine-in service. Both respondents also listed their businesses on all three major third-party delivery platforms at the start of the pandemic. Though they were disgruntled with the high fees charged by these platforms, delivery was characterized as a necessary lifeline that provided increased exposure for the business. Neither respondent adopted in-house delivery or alternative options due in large part to staffing shortages and not having the time or capital to look into smaller platforms and take a chance on them. Additionally, neither business was listed on any of the popular Chinese-language delivery services like HungryPanda and Fantuan due in large part to the demographics of their customer base (Guo). Both businesses also report that prices for their supplies increased noticeably.

Daniel’s business was fully closed from March to June 2020 and both restaurants remained closed to indoor dining even when restrictions were lifted in Toronto, citing concerns over the safety of their staff and patrons. Particularly due to the pandemic’s reduction of staff, this decision may be connected to the fact that a significant proportion of their personnel are family members or close family friends.

Linda, who also works full-time in a corporate role, has been working seven days a week due to the necessity of having to juggle two jobs. Both restaurants have also had to dedicate a significant amount of time and resources to introduce additional safety measures like temperature checks, increased sanitation, and plexi-glass screens at the counter. Daniel’s business has been able to recover thirty percent of its monthly expenses through government aid and rent relief initiatives, while Linda has not had the time to apply for them due to her busy schedule and the complicated process involved in applying for these grants.

An issue experienced by Indian-Hakka restaurants and many other ethnic food businesses was the continued expectation placed upon them to offer affordable fare. The proprietors of Yueh Tung, Toronto’s oldest Indian-Hakka restaurant, said in an interview with Toronto Life that “everybody expects Chinese food to be cheap” (Liu and Liu). Golden Joy, for instance, is known for offering generous meal-sized portions with a drink for no more than eight dollars (Shephard). The business model of Indian-Hakka restaurants is predicated on high sales volume, which makes them particularly susceptible to struggling as a result of the restrictions imposed by the pandemic. Moreover, the potential closure of affordably-priced restaurants poses a significant threat to the food-insecure residents that patronize Indian-Hakka restaurants.

Singapore Rice Noodles, a dish served at Golden Joy that is prepared by using curry powder to season vermicelli.

Yueh Tung also has had to deal with anti-Asian xenophobia in the form of people refusing to dine at their restaurant for fear of contagion from Asian foods or more banal forms of racism like being questioned if they import foods from China (Liu and Liu). These businesses have been able to remain resolute in spite of these difficulties because of the vocal support they have received from community members. When I asked Linda if she had encountered any cases of anti-Asian racism directed at her business, she replied with this anecdote:

“Not really, my customers actually are my cheerleaders, always cheering us on. However, there was an instance during the early stages of the pandemic, where a child told his dad that they should not eat Chinese food anymore. The gentleman so patiently sat the child down to explain what it was and how they need to support us. Till this day, that gentleman ensures that he orders from us every Saturday.”

She also recounted numerous instances of how her customers have gone above and beyond to support their business by donating homegrown vegetables and PPE, lining up at grocery stores for them, providing social media tips, and offering to distribute flyers. Customers have explicitly stated to her that they elected to pick up their orders in-store as opposed to opting to use third-party delivery services because they learned about the exorbitant fees charged by these platforms. Yueh Tung has established an alternative source of revenue inspired by suggestions from their customers. They have started to bottle and sell the sauces from some of their most famous dishes, branded under their restaurant’s Vooka line named after the Hakka word for “home.” Though they had considered selling their sauces prior to the pandemic, they did not have the time or capability to actualize the idea until the early months of the pandemic freed them up. The bottled sauces can be purchased at the restaurant’s storefront or at Bombay Bazaar, an Indian grocer in Markham (blogTO).

Instagram advertisement by Yueh Tung for their Vooka line of sauces, available for online order and delivery, at their restaurant storefront, and numerous independent grocers across the GTA.

Conclusion

Linda and Daniel’s experiences share many commonalities with the broader narratives attributed to restaurants during the pandemic in the media — high delivery fees, increased expenses, and safety concerns featured prominently in the stories they told me. Through the interviews I conducted, I learned that in order to survive the pandemic, these businesses were dependent on their staff going above and beyond their normal workload by adding new responsibilities on top of their old ones. Both Linda and Daniel expressed a deep appreciation for the way their customers have backed them through their patronage, as well as for the random acts of kindness made in support of their businesses. The personal, humanistic elements of these stories is something that is often absent in media coverage of the pandemic. Indian-Hakka restaurants developed a cuisine to satisfy the appetites of cultural outsiders, so it is fitting that a spirit of persistence and broader community support has been integral to their survival during the pandemic.

*All rights to this reflection are reserved to the author/Feeding the City. It cannot be republished without express permission . Contact at jeffliu.liu@mail.utoronto.ca or feedcity2020@gmail.com

Bibliography

Chiu, Shirley. “Ethnic identity formation: A case study of Caribbean and Indian Hakkas in Toronto,” MA diss. York University, 2003.

Guo, Jackson Yue Bin. “Food and Toronto’s Chinese Community through COVID-19.” Feeding the City. University of Toronto, August 27, 2020. https://www.utsc.utoronto.ca/projects/feedingcity/2020/08/27/food-and-torontos-chinese-community-through-covid-19-by-jackson-yue-bin-guo/.

Lau Anusasananan, Linda. The Hakka Cookbook: Chinese Soul Food from around the World. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012.

Li, Mu. “Performative Chineseness and Culinary Tourism in Chinese Restaurants in Newfoundland, Canada.” Folklore 131, no. 3 (2020): 268–91.

Liu, Haiming. “Chop Suey as Imagined Authentic Chinese Food: The Culinary Identity of Chinese Restaurants in the United States.” Journal of Transnational American Studies 1,

no. 1 (2009).

Liu, Jeanette, and Joanna Liu. “‘We Will Not Be Able to Bounce Back If We Have to Shut Down’: How One Chinese Restaurant Is Coping with Coronavirus.” Toronto Life, March 18, 2020. https://torontolife.com/food/we-will-not-be-able-to-bounce-back-if-we-have-to-shut-down-how-one-chinese-restaurant-is-coping-with-coronavirus/.

Oxfeld, Ellen. “Still Guest People: The Reproduction of Hakka Identity in Kolkata, India.” ChinaReport 43, no. 4 (2007): 411–35.

Shephard, Tamara. “Golden Joy Serves Authentic, Affordable, Customizable Hakka in Etobicoke.” Toronto.com, November 6, 2019.

Xing, Zhang. “The Bowbazar Chinatown.” India International Centre Quarterly 36, no. 3/4 (2009): 396–413.

Xing, Zhang, and Tansen Sen. “The Chinese in South Asia.” Essay. In Routledge Handbook of the Chinese Diaspora, edited by Chee-Beng Tan, 205–26. London: Routledge, 2018.

“Yueh Tung in Toronto Has Started Bottling That Famous Chili Chicken Sauce.” blogTO, December 9, 2020. https://www.blogto.com/videos/yueh-tung-toronto/.