by Matilda Dipieri, Junior Researcher

“[T]his moment of time, right now, there’s the opportunity to shift or nudge how things are operating…and to change cultures and habits, not just with farmers, but with people enjoying food” — Dave Kranenburg

The Virtual Farmers Market, also known as the Green Circle Food Hub, was founded by Dave Kranenburg and Emily Tufts from Kendal Hills Farm, near Orono, Ontario. It arose from the initial shock and disruption brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Faced with losing 95% of their revenue in the last week of March 2020, and the first week of the pandemic closures in Toronto, these farmers quickly searched for an alternative to save their business and their farm.¹ Mostly through word of mouth and contacting community members, they set up an online platform that brings together dozens of local food producers and connects each vendor’s products to consumers (or “eaters”) around the GTA, through weekly, streamlined deliveries.

Fortunately, the initiative continues to thrive since its launch in March 2020.

Having brought in $1.3 million in revenue in its first 37 weeks of operation, the Virtual Farmers Market has shown tremendous success in its adaptation to these challenging circumstances.² With over 60 producers selling over 400 different products on the online market’s storefront, consumers can support operations offering everything from fresh and heirloom vegetables to Indigenous and foraged foods to specialty hot sauces and freshly baked goods.³ And all of the products are aggregated from local producers and delivered directly to customers’ doorsteps.

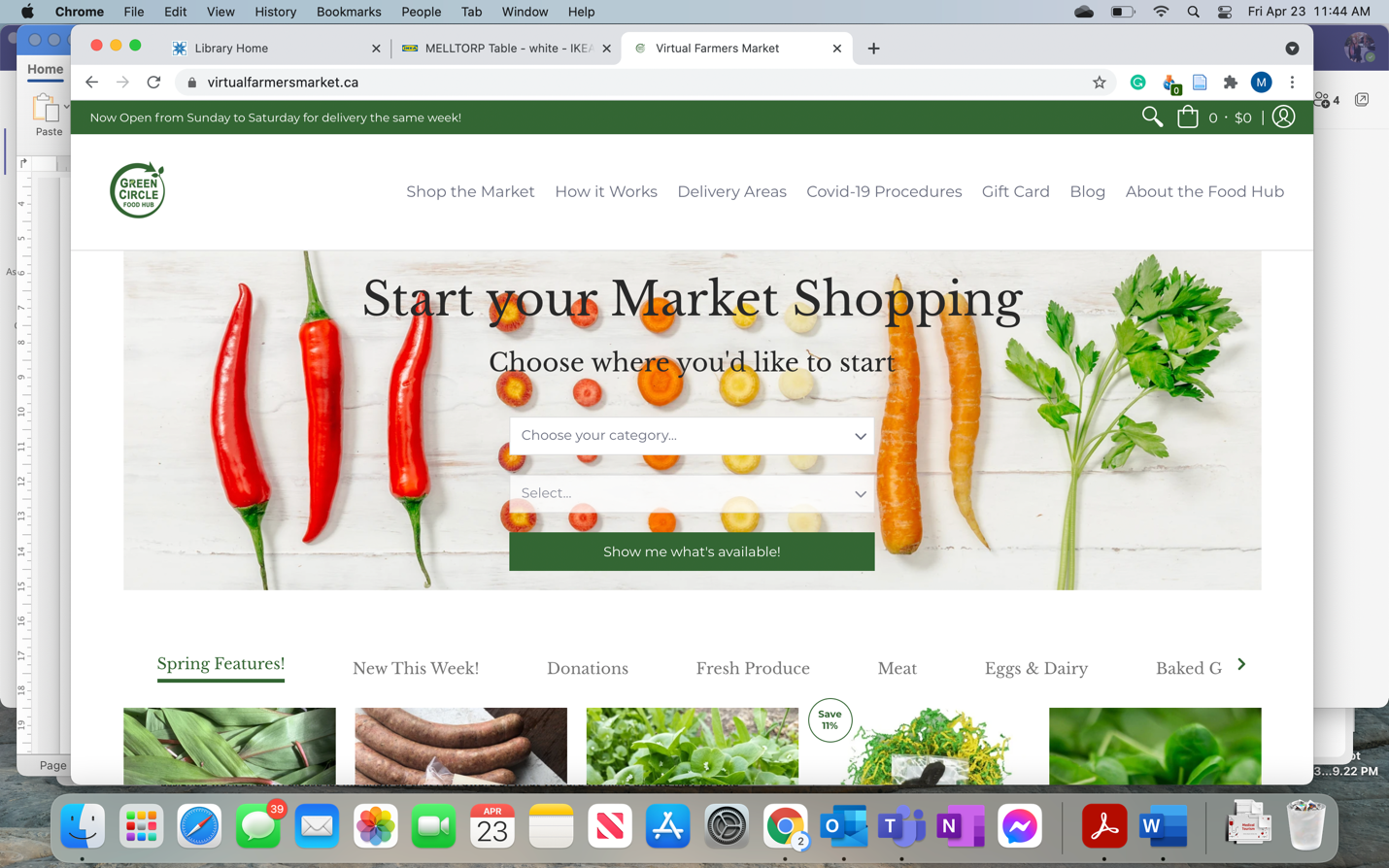

The Virtual Farmers Market’s online platform (Photo: Virtual Farmers Market)

While boasting convenience and variety for consumers, most of all, the Virtual Farmers Market is helping to address a longstanding flaw in our food system: the problem of the “missing middle.”

A majority of Canadian farmers with small-scale operations face several logistical challenges in terms of marketing infrastructures and distribution approaches to ensuring that their products can reach consumers. Whereas Canada’s larger farms tend to enter into long-term contracts with corporate retailers and wholesalers, marketing and distribution can be complicated and labour-intensive for smaller-scale producers.⁴ From the perspective of these farmers, the options available to sell and distribute your goods have always been limited. According to Dave Kranenburg, “farmers have long faced a gap between large-scale, wholesale distribution and [traditional] farmers markets. There’s a different way to get food to people that allows farmers to spend less time on the road, in their trucks delivering the food, and more time in the field growing it.”⁵ Here, Kranenburg is referring to the fact that smaller producers tend to shoulder the entire burden of looking after the logistics of getting their food products to customers. This can require incredible amounts of time and energy coordinating, for example, deliveries to restaurants or direct sales to individuals and families through farmers markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programs.

Ramps, or wild leeks from Clearwater Farm, and a medley of grown and foraged mushrooms from Kendal Hills Farm, now available on the Virtual Farmers Market website (Photos: Virtual Farmers Market)

As a rapidly developed response to the immediate challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the longer-term challenges associated with food marketing, at its core, the Virtual Farmers Market ensures that “a farm’s ability to grow is [no longer] limited by a farm’s ability to sell.”⁶ Giving credit to small-scale producers’ ability to feed significant portions of the population, this initiative creates an improved pathway for them to do so, responding to the immediate challenges of the pandemic and creating what has thus far proven to be a robust marketing system that is helping to fill the “missing middle” of food infrastructure. It helps that this initiative is coordinated by farmers themselves. Kranenburg and Tufts know that some farmers will want to continue directly marketing their food to customers, but that many will continue to benefit from support and cooperation in terms of marketing and distribution. In establishing the Virtual Farmers Market, they have created a way of connecting small-scale farmers to more people, without the burden of each farmer having to take on the role of grower, marketing agent and delivery person—as has typically been expected in the past. Enabled by the Virtual Farmers Market’s online software, Kranenburg and his team can combine products from multiple vendors into customized orders, with a single delivery truck making more efficient distribution to individual homes.

Having grown in success and support over the past year, the Virtual Farmers Market continues to respond to the changing needs of its loyal customer base and the community of producers it has created. With a waiting list that has grown to over 50 interested vendors, the Market insists on including any small-scale farmer or food processor, regardless of whether their products are certified organic, or not. Illustrating the diversity of small-scale production, the Virtual Farmers Market leaves it to consumers to make a decision about which vendors to support. Serving solely as a much-needed middle infrastructure, the online market provides details about who is providing each of the products sold through the platform, so that users and eaters can perform their own research into vendors.

Vegan Momos from TC Tibetan Momos, and Pretzel Bagels from Spent Goods, now available on the Virtual Farmers Market website (Photos: Virtual Farmers Market).

Small-scale producers will continue to face challenges in competing with larger farms and corporate food retailers, in terms of cost and convenience, as well as in adapting to people’s rituals around food provisioning, but as the Virtual Farmers Market has shown, viable alternatives have emerged. The quality and variety offered by online platforms such as this are unparalleled, particularly as these options are more likely to offer great tasting food that better supports ecological food systems and producers’ livelihoods. With warmer months approaching, the Market is currently offering a great variety of springtime cultivated and foraged produce, such as Ontario radishes, ramps (wild leeks), microgreens, mushrooms, and spring onions, as well as locally produced maple syrup, and a diversity of prepared foods such as Tibetan momos, German-style pretzels, pitas and Greek dips. Through the Virtual Farmers Market’s system of pre-orders, farmers are freed from the uncertainty of direct selling only at seasonal farmers markets, allowing them to focus on what they do best: producing delicious, flavourful foods.

Potato gnocchi made with local russet potatoes and flour as well as the first of the season Virtual Farmers Market ramps for the pesto sauce (Photo: Piya)

Footnotes:

[1] Battaglia, J. (Director). (2020). COVID 19: The Future of Food [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.nfb.ca/film/covid-19-the-ture-of-food/ [2] Local Food and Farm Co-Ops. (2021, March 10). Farming in COVID: Farming, Labour and Food Distribution (Dave Kranenburg). In Local Food and Farm Co-ops Assembly: Resilience. Retrieved from https://www.localfoodandfarm.coop/assembly-program [3] Ibid. [4] Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario. (2020, November 30). Distribution that Fits: Finding the best distribution model for your farm (Dave Kranenburg). In Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario Conference: Reaching & Rooting. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/487707379/edb43a2530 [5] Ibid. [6] Ibid. In addition to the sources listed here, this article was also informed by a personal interview with Dave Kranenburg (April 9, 2021).