An alum’s massive, 80-inch self-portrait will permanently hang at U of T Scarborough thanks to students in a unique course.

Created by photographer Mariam Magsi (BFA 2008 UTSC), Kabilay ki Baiti (Daughter of the Tribe) will join more than 150 artworks displayed around Scarborough through the Doris McCarthy Gallery’s (DMG) permanent collection. Every two years, students in the studio arts course “Curatorial Perspectives II” select a new piece for the collection.

“The history of photography is deeply colonial,” Magsi says. “With recording tools in our hands, we are documenting our humanity with dignity and respect.”

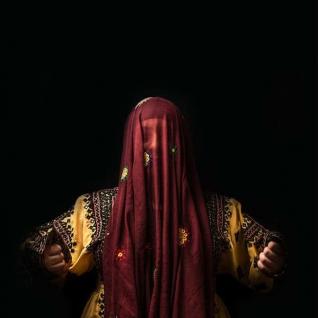

In Daughter of the Tribe, Magsi is dressed in garments hand-stitched by her ancestral people, the Magsi clan. Over seven photos, she gradually performs a hand gesture the group uses to show devotional love, called mai sadway jawan in Urdu. It means: "I sacrifice myself for you."

“In this piece, I’m actually performing the gesture for myself, while channeling what I have learnt from ancestors,” says Magsi. “These kinds of gestures are active, but I'm also forgetting them. And I'm not the only one.”

The Magsi clan is a subset of the Baloch people, who speak Balochi and inhabit the Balochistan region in Pakistan. They’re known for their intricate, hand-made clothing, which Magsi has used to reconnect with her paternal ancestry. She’s even noticed recurring shapes in the embroidery that illustrate the group’s way of life, such as chicken feet and flower petals.

“It’s very interesting to see communication and language happening through embroidery,” says Magsi, who often wears Balochi clothing to events. “I’m trying to bring the clothes from the performative to the functional, but it’s telling that I find Western clothing more comfortable than those from my culture.”

Magsi wears an embroidered veil called a chadar in her self-portrait; much of her work explores Western reactions to Islamic clothing. Though she grew up in Pakistan, a majority Muslim country, Magsi went to a Catholic school. She still remembers the day a teacher cut a student’s necklace off because it had an Islamic symbol. Now a dual citizen of Pakistan and Canada, she’s seen family members harassed in Toronto for wearing traditional clothes.

“I'm in between all of these worlds trying to fight them but also trying to understand them,” she says. “It's a very interesting space to be in. It has a lot of complexity and nuance, and you can often be an observer, a witness.”

Magsi, who first came to Canada as an international student, believes her story was what resonated with students in “Curatorial Perspectives II.” In her talk with the class, Magsi also revealed she took the photos for Daughter of the Tribe herself in her bedroom using only a few lights, a black backdrop and a remote trigger for the camera.

“The world is your studio. You don't need a lot of people or money and you can still create powerful impactful work, and through the online world it has a global reach,” she says.

Class turns students into curators, artists into lecturers

Armed with research, a budget and a shortlist of artists, students chose Magsi’s work in last fall’s edition of the course. It was taught by award-winning artist and visiting lecturer Anique Jordan, whose own art was chosen for the permanent collection by students in a past course.

“The students were really careful with how they made their decision and then really strong with how they advocated for what they thought was important,” Jordan says. “I think it was the meaning behind the gesture in Daughter of the Tribe that resonated.”

The course was created in 2015 by Ann MacDonald, executive director and chief curator of the DMG. MacDonald has a rule for who ends up on the shortlist given to students: the artist needs to have past or present connections to Scarborough or a body of work that illustrates the cultural landscape of the eastern GTA (though this limitation didn’t apply to Indigenous artists).

“The course is part of the awakening as to how special Scarborough is, and the creative force within the artists who live here,” says MacDonald. “The focus of the course is on building sustainable relationships, rather than competition.”

At nearly seven feet wide and one-and-a-half feet tall, Magsi’s will be one of the longest pieces in the DMG’s permanent collection, which has grown to more than 1,700 objects in its almost 60 years. It will be displayed at U of T Scarborough following a custom frame job.

“It's such a full circle. This is where my journey as a migrant began as an international student,” Magsi says. “To have my work up there with me in it, it just adds all these layers. It’s very powerful and I can't wait to see it in person.”