Researchers from the University of Toronto have released a study examining how to help Sixties Scoop survivors reconnect with their Indigenous culture.

The study, co-authored by UTSC Health and Society Professor Anita Benoit, Maggie Campaigne, a Community Engagement Worker from YWCA, and research assistant Janani Kodeeswaran, conducted an 8-week series of sessions at an urban housing facility in Toronto which supported Sixties Scoop survivors to increase their cultural knowledge through engagement with Knowledge Carriers, working up to participation in a full moon ceremony.

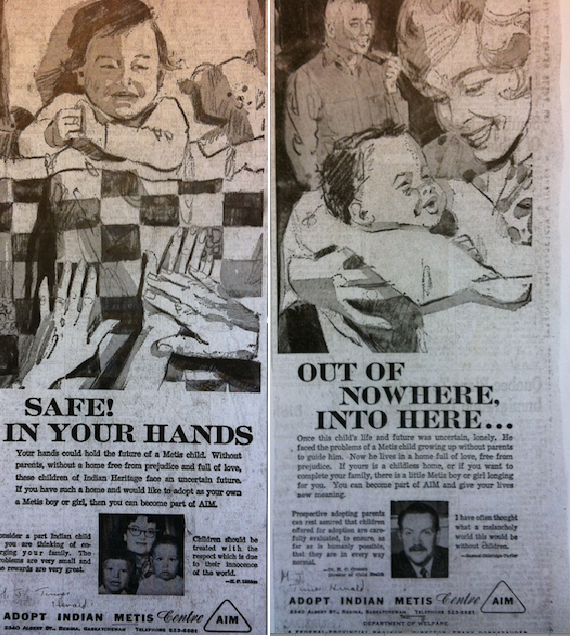

The project emerged from the disconnectedness felt by some of the women living in the urban housing facility to their culture, many of whom had experienced the trauma of being removed from their families during the notorious “Sixties Scoop,” which saw at least 20,000 Indigenous children forcibly sent to foster care or adoptive homes in Canada, the US, and overseas between the 1950s and 1980s.

This has resulted in many Sixties Scoop survivors experiencing a lack of connection to their Indigenous culture, which in turn has been linked with adverse health outcomes. Some of the women who had tried to engage with their Indigenous culture felt uncomfortable or embarrassed by their lack of knowledge. The project aimed to counter this by creating a space for sharing cultural knowledges and working with Knowledge Carriers to build individual and collective cultural knowledges.

“The idea was rather than being inclusive of Indigenous culture, that we do something that was instead grounded in Indigenous culture,” explained Prof. Benoit. “We wanted to bring in a lot of different Knowledge Carriers, Elders, grandmothers, grandfathers, and cultural teachers to provide a number of different teachings.”

The program had a positive effect on the women and their general feelings of wellbeing. It also gave them the confidence to continue learning more and take part in ceremonies. “During the two cycles both ending in full moon ceremonies, the women felt more confident, more comfortable practicing the full moon ceremony,” said Prof. Benoit. “The fact we introduced them to a variety of different Knowledge Carriers increased their connection to the community outside of their organization. Now they know people and can go out to the ceremonies led by specific Knowledge Carriers.” They also presented the women with the tools they would need to participate in ceremonies, such as a copper goblet, abalone shell, feast bundle, medicines, or a ribbon skirt and explained the cultural significance of each item.

Women participating in the study took part in focus groups, in which they described the lasting effects the Sixties Scoop had on them, particularly with regards to mental health. They further expressed their longing for more involvement and knowledge of Indigenous cultural practices. They also expressed deep concern about the ongoing Millennial Scoop, the current overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the Canadian child welfare system beginning in the 1980s. “The women in the study were concerned about it because it impacts them, even if not directly then they all know a friend or family member affected by it,” noted Prof. Benoit. “The goals of the Sixties Scoop were to do something the Residential Schools couldn’t do, to create a permanent kind of rupture between the child, their community, and their family. The Millennial Scoop is creating that kind of permanent rupture, but it’s also retraumatizing people who went through the Sixties Scoop all over again. It’s their kids, and their grandkids.”

Prof. Benoit will soon begin a longer-term project, this one six months long, aimed at reconnecting Indigenous women to their cultures and further measuring the effects on health and wellbeing. The extended timeframe is important because perseverance is key to building confidence.

“You’re not going to be perfect after one or two sessions,” noted Benoit. “For some women there was distance because they didn’t know where their communities were. They were disconnected from their families, and that caused them to feel a little bit cautious or even scared during ceremonies because they didn’t know quite what to do and they didn’t want to be disrespectful. There were little things that most Indigenous people would know how to do, that some of the women didn’t, so it made them more hesitant to participate. But because of the space we had created we were able to introduce them to all these little things that they had seen, but they didn’t always quite understand why people did them. We were able to make them comfortable and as the Knowledge Carriers said you absorb the things you are ready to learn at your own pace, so if you don’t understand something now, that’s OK, it takes continued practice.”

Pictured: Newspaper ads for the Adopt Indian and Métis Program, Saskatchewan, late 1960s.