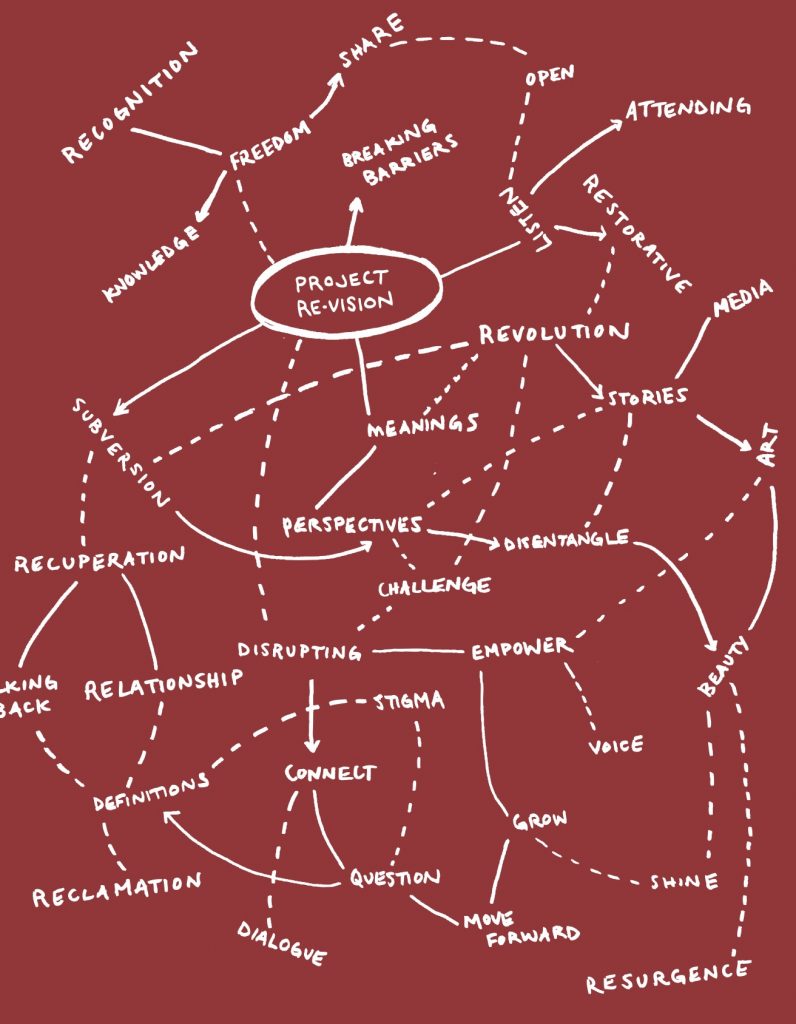

Post by HLTD50 student SickSocietiesFromThe6

One of the most inspiring and informative experiences that I had in the HLTD50 course was when I had the opportunity to create a digital story with the help of Dr. Charise and the Project Re•Vision team. On the first day of the workshop, Dr. Carla Rice talked about stories as “constructions,” noting that stories are representations of reality – that they are never the full reality. She also emphasized the importance of stories because she explained that stories are all we are. I ruminated about what it meant for stories to be all we are. I thought about vulnerability and how difficult it feels for me to share personal stories – stories that make me cry, stories that make me uncomfortable, stories that do not have happy endings, stories that I do not discuss. If stories are all that we are, I wondered whether I was missing out on forming fulfilling human connections that I could have had if I shared a story that I was afraid of sharing.

*

To be vulnerable means to be open to the possibility of being wounded. It means letting your guard down. It means stripping yourself of your own self-judgment and peeling back layers of what you are concealing. When I tell a story – when I tell my story – I am vulnerable. While I am opening up to criticism and judgement, I am also opening up to inspiration and reflection. I thought about what this meant in relation to digital storytelling. Digital storytelling crafted a space to be vulnerable. It was a medium of storytelling in which I, as a storyteller/creator, could claim a position and resist the dominant discourse.

I think about the permanent nature of digital storytelling. These digital stories, with consent, can be played over and over again to different audiences. These stories of resistance stay. They are not silenced, they are not swept under the rug. They are permanent and they are heard. There is a different layer of vulnerability and human connection that comes from sharing a story in a digital format because of its permanent nature. In the context of healthcare, I truly believe that digital storytelling practices can help healthcare providers to develop meaningful relationships with healthcare users. Typically, healthcare institutions perpetuate strong hierarchical relationships between physicians and patients, in which patients are subordinate and must obey physicians. Patients are often seen as being one-dimensional because they are solely viewed and understood in relation to their disease or condition. Likewise, physicians are often viewed as being one-dimensional because they are viewed as people who can restore patients’ health. Undoubtedly, no patient is only a patient and no doctor is only a doctor. However, it is difficult to dismantle the one-dimensional notions that are associated with such positions, especially as they relate to positions of power.

One aspect of creating humanizing practices and interactions in the healthcare system is to use digital storytelling as a way of dismantling the one dimensional views of people who take part in healthcare, whether they be healthcare users or healthcare providers. Since digital stories claim a position against the dominant discourse, they help to humanize people because every individual is seen as being multi-faceted and complex, instead of merely being viewed in a one-dimensional point of view.

Since the digital story responds to a dominant discourse, employing tactics of resistance in particular, creators of digital stories can express that they do not solely inhabit one identity. Physician-hood and patient-hood becomes aspects of individual positions instead of over-encompassing identities that exist in binary categorizations.

*

The challenging aspect of creating a digital story is being vulnerable. The possibility of being wounded arises. The storyteller needs courage to open up about their voice, authority, and positionality. But being vulnerable is downright terrifying.

When I was creating a digital story, I was afraid of opening up about my experiences with mental illness. I thought about all of the ways in which I could get hurt or I could hurt others. I wondered:

What would people say or think?

Would I be doing my community a disservice by sharing my struggle – a struggle that they took part in creating?

How did I know that my story was being truthful to my reality?

How could I articulate my story in a way that was personal but also relatable, to some extent, to others?

Stories are constructions. Every story is a representation of reality. Stories are important because they are inherently reflective about how one constructs their reality and understands their surroundings, circumstances, and experiences. I was opening myself up to the possibility of being wounded. I was coming from a place of introspection when I shared my story. For the digital story, I decided to talk about my experiences with major depressive disorder and how my experiences and feelings were at odds with the rhetoric of self-care. I talked about how I felt reading articles that told me to eat healthier or exercise. These articles assumed that I woke up every day with a will to live.

I wondered about what self-care looked like for a depressed person.

I am still trying to figure this out.

The readers and writers who engaged with the self-care rhetoric have dominant voices, voices that typically cater to people who do not experience mental health issues. This discourse shaped my own story because it made me reflect upon how self-care looked different for every individual. The discourse negatively impacted my story about how self-care manifests as a someone with depression, because I was, and am, bombarded with messages of what it looks like take care of myself.

Throughout the process of creating the digital story, I found a voice through which I could make sense of my experiences, and reflect upon how vulnerability paves way for conversations that need to take place.